Every zeitgeist has its drug.

That’s the secret code, the tracer bullet through history. You don’t chart the eras by wars or presidents or hairstyles — you chart them by the highs. By the chemicals, rituals, and psychic contraband that lit the fuse and kept the engine howling.

You want to know what decade you’re in? Don’t check the headlines — ask what gets people out of bed in the morning and keeps them up at 3AM. That’s your drug. That’s your god.

And here’s the trick: the real freaks, the smellers of the zeitgeist, the antennaed mutants who twitch when the wind changes — they can tell when the high is dying. They sniff it in the air like dogs before a storm. They know when the supply’s running dry, when the thrill’s going limp, when the culture’s just going through the motions like a junkie reciting affirmations in a bathroom mirror.

The drug and the zeitgeist — they rise and fall together.

Acid in the ’60s, coke in the ’80s, Prozac in the ’90s, Adderall in the startup aughts.

Each one a perfect match for the collective nervous breakdown of its era.

Not chosen by taste — chosen by need.

And now?

Now we’re running on dopamine. Pure, digital dopamine — drip-fed by devices, delivered by screens, optimized for endless scrolls and performative personas. And the high?

It’s narcissism.

Self as product. Self as brand. Self as a constantly reissued press release.

Main character syndrome with a six-ring circus of side plots and skincare routines.

But something’s wrong.

The flavor’s off. The high’s gone cold.

The clowns are crying and the likes don’t hit like they used to.

You can feel the culture twitching, stuttering, staring into the mirror and wondering why it suddenly feels like work to be seen.

Narcissism is on its way out.

Bigly.

And with it, the dopamine machine is starting to sputter.

Not gone — not yet — but the cracks are showing.

The sell-by date’s been printed.

The freaks are already moving on.

What comes next?

God knows.

But we’re here to light the autopsy table, pour a stiff drink, and document the final spasms of the world’s last great ego trip.

THE PERFECT DRUG

I always said: buy the ticket, take the ride. But in that flaming wreck of a free market, the ticket booth had been manned by sociopaths in startup hoodies, and the ride turned out to be a haunted carousel fueled by Adderall and venture capital.

Here was the grinning secret every third-rate wizard of Silicon Valley knew but wouldn’t say out loud: you didn’t need a good idea — you just needed a target. Preferably one with a mild-to-moderate psychological disorder. Nothing too crippling — just a manageable cocktail of insecurity, addiction, and digital trauma. The kind of folks who used to buy X-ray specs from the back of comic books and were now forking over $39.99 a month to “optimize their dopamine.”

You found those people. You spoke their language. You promised transcendence in twelve easy payments.

Then you lied.

You lied like the Pope in a brothel. Lied like your Tesla depended on it. You told them you had the cure, the hack, the cheat code, the goddamn answer to their late-night doomscrolling despair. You said their anxiety wasn’t a problem, it was potential — a feature, not a bug — the golden key to creativity, enlightenment, or at the very least, better abs. You wrapped it all in soothing gradients and semi-scientific fonts. You called it “self-care.”

That had been the racket. That was the hustle. Not innovation — manipulation. Not progress — persuasion.

And they thanked you for it.

Hell, they subscribed.

A FEAST OF THE DAMNED

Appetizers are for dilettantes and TikTok therapists. You want the main course, friend? Pull up a chair. Light something unfiltered. Let’s carve the beast.

The true pros—the top-shelf operators in this meat grinder of a republic—don’t just identify neuroses, they cultivate them. They water them daily with fear, guilt, curated envy, and a steady drip of dopamine-branded despair. They don’t sell solutions; they sell symptoms with a dashboard.

Want to feel connected? Here’s a social network built to destroy your attention span and monetize your loneliness. Want clarity? Here’s an app that tracks your thoughts like an Orwellian Fitbit and sells them to hedge funds in Singapore. Want meaning? We’ve got twelve different gurus live-streaming from Bali on how to turn your trauma into passive income.

It’s not a market anymore. It’s a menagerie.

Every user a case study. Every swipe a confession.

And the high priests of this new digital tabernacle?

They know exactly what you want before you do.

This is the meal. This is what we’re all chewing on:

Processed dreams, sprayed with synthetic hope,

served on biodegradable platitudes with a side of algorithmic slop.

And we keep eating.

Because the thing about noble lies—real, juicy, professionally engineered noble lies—is that they’re more comforting than truth. Truth demands something. Lies tuck you in, kiss your forehead, and offer you 10% off with a promo code.

Success, in this twisted empire, isn’t about building something beautiful. It’s about scaling delusion. Manufacturing identity crises in bulk. Gaslighting as-a-service.

And if you do it really well?

You get a TED Talk.

You get a podcast.

You get a VC-backed brand of artisanal nootropics made from moonlight and ketamine.

Bon appétit, America.

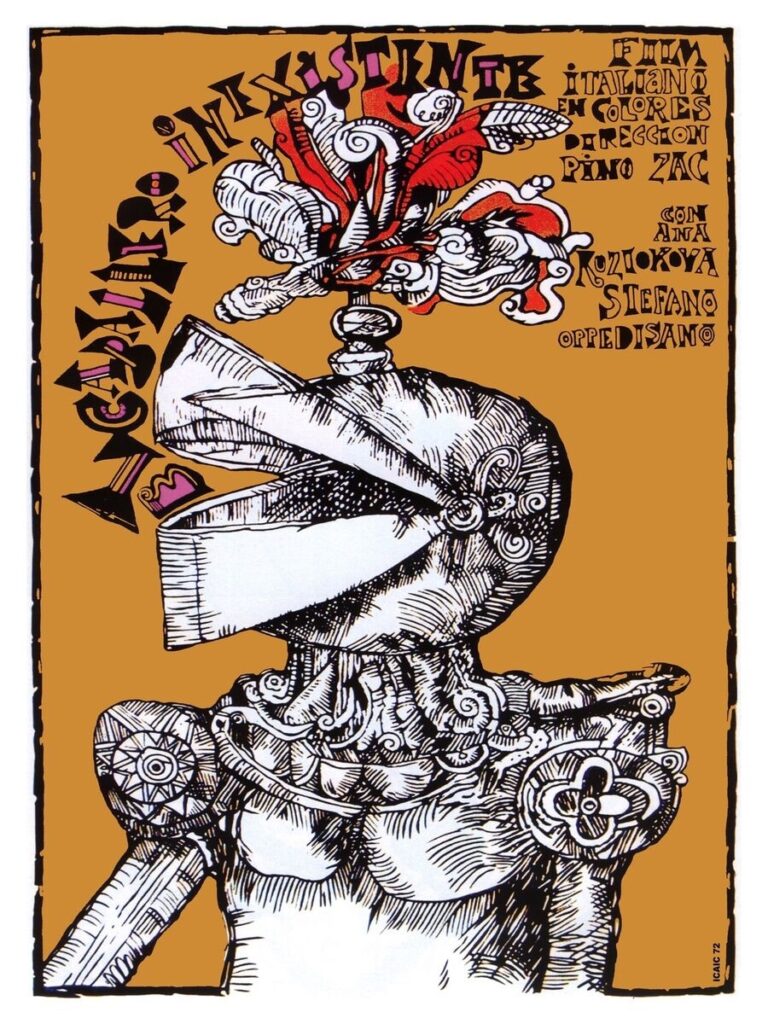

OPIUM

Was alcohol better than opium? Christ, that’s like asking if being mauled by a bear is better than drowning in a warm bath. Both’ll kill you — the only difference is how poetic your obituary sounds.

Back in the glory days — when men were men, and bars were confessionals soaked in cigarette ash and whiskey stink — we drank to obliterate. To see God, or at least forget that He stopped returning our calls. Booze was democratic. Available. American. It didn’t require a login, a subscription, or an influencer with a collagen sponsorship. You belly up to the bar, throw down a bill, and gamble your liver on the warm hope of temporary amnesia.

But opium — ah, that silky serpent — that was a different beast. Opium was mythic. The choice of romantics and revolutionaries. You didn’t do opium to forget — you did it to float. To become a ghost in your own skin. A poet without a pulse. It whispered to you, wrapped you in gauze, and lulled you into a dream where the rent was paid and the wars were over.

Now? We don’t need either. We’ve synthesized both.

Liquor is an app.

Opium is a feed.

Despair is user-generated and monetized by the click.

We are self-medicating on serotonin loops and cybernetic shame spirals. Dopamine drip-fed through likes, swipes, retweets, and targeted outrage. Forget the needle. Forget the bottle. The new high is being seen. Or believing you’re being seen. Same difference.

And the comedown? Oh, it’s clinical. Sterile. You don’t wake up in a gutter anymore. You wake up with 137 unread notifications and a sinking suspicion that you sold a piece of your soul for a blue checkmark and some mid-tier engagement.

So was alcohol better than opium?

Was either better than this current hell-broth of digital anesthesia?

Debatable.

At least the old poisons had taste.

Now we overdose on blandness.

On soft, slippery lies piped in 4K resolution, narrated by friendly robots with dead eyes and helpful tips.

Progress? Maybe.

But I’d trade all the smart tech and lifehacks for one more night drunk on gasoline and thunder, yelling poetry at the moon and chasing demons through the desert on a stolen motorcycle.

At least that felt like living.

But I too felt it at the time. Jesus, how could you not? The air was thick with it — not love, not hope, not even the usual cocktail of fear and masturbation — but meaning, man. A cheap, nasty strain of counterfeit meaning passed around like bathtub gin at a dying wedding. That was probably as good as it was ever gonna metaphorically get — the highwater mark of the American hallucination, just before the lights flickered and the rats started wearing AirPods.

I felt it in my teeth.

I didn’t see it coming — I felt it, like a bad drug turning in your bloodstream. A sudden wrongness in the high. The buzz that used to carry you suddenly collapsing under its own weight, leaving only the tremors and dry mouth. That was the first sign: the drugs didn’t work anymore. Not the literal ones — though those, too, started feeling like sugar pills wrapped in marketing — but the psychic drugs. The idea of being in a band. The myth of independence. That whole beautiful, blood-soaked lie we told ourselves in the ‘90s: that if you stayed weird and played honest, the world would eventually catch on. That was the trip. And for a while, it worked. Long enough to believe it. But then the high wore off, and I started to feel the cracks in the culture. No explosions, no warnings — just a slow evaporation of meaning. I didn’t have a grand vision of the collapse; I wasn’t perched on the edge of the digital apocalypse with a bullhorn and a bag of mescaline. But I knew. I felt it in green rooms and gas stations, in the hollow eyes of promoters who used to give a damn. The strange dead air after shows. The numbing echo of a thousand songs floating into algorithmic purgatory. Everything started feeling performed, like we were all auditioning for something that had already been canceled. And somewhere in that haze, I realized: the independence we built our whole identity around had been monetized, dissected, branded, and sold back to us with a monthly subscription fee. And we took it. Willingly. Like pigs at the trough, grinning with slop on our faces.

It was peak-fantasy realism, and you knew — like a hungover prophet in a desert of discount self-actualization — that the whole thing was seconds from rot.

And now

I’ve been around long enough to smell a trend going rancid. I’m a trader in sell-by-date narratives, baby. I know when a drug’s about to get unfashionable.

That’s why I can tell when someone’s drugs starts to wear off. That is what is happening now.

That’s it. That’s the whole twisted truth, boiled down to a grim little shard of instinct: I can tell when someone’s drugs start to wear off. It’s not subtle — it’s a psychic shiver, a short-circuit in the rhythm. In the glowing eyes of every party ghoul and tech grifter In the shaky hands of washed-up Instagram therapists and mushroom microdosers trying to rebrand as prophets.

Their eyes don’t dance the same. Their speech stutters in the corners, like an old car with bad brakes coasting downhill into the future. That hollow conviction, the frantic energy of someone trying to outrun the comedown. And that’s what’s happening now. Culturally. Spiritually. Across the board. The dopamine drip is sputtering, and all the pretty plastic people are starting to twitch. Their hits don’t hit. Their affirmations don’t affirm. The mirror stopped loving them back. You can see it in the timelines and the TikToks — the grins are just a little too wide, the messages a little too desperate. They’re not on top of the wave anymore — they’re under it, holding their breath and hoping no one notices the panic in their filtered eyes. The supply is poisoned. The high is broken. And now we’re all just waiting to see who snaps first.

You could see the come-down coming like a freight train full of Buddhist MLM consultants.

Ketamine, mindfulness, ayahuasca in a tent with a man named Derek —

all of it part of the same desperate crawl toward meaning in a culture that had already pawned its soul for engagement metrics.

And the great monster of it all — the cracked-out vampire lurking behind the whole glittering facade — was narcissism. Not the old-school Elvis kind, with rhinestones and charisma. I mean the bloated, ghoulish, app-optimized narcissism that came standard with every smartphone and a front-facing camera.

But even that is fading now.

You can feel it — like a drop in barometric pressure before a cyclone of cultural malaise.

Narcissism is going out of style bigly.

The zoomers want sincerity. The millennials are burned out from performative selfhood. Even the crypto bros are weeping into their Ring lights, begging for forgiveness from God and the SEC. The tides are turning. The mirrors are cracking. And all the old freaks who made a killing in the age of the self are waking up to find the market flooded with remorse and AI-generated poetry.

No more dopamine-on-demand.

No more selfies as sacrament.

No more influencer-gurus hawking trauma as lifestyle.

We are entering the post-narcissist hangover —

a national come-to-Jesus moment where everyone looks in the mirror and sees a sponsored ghost.

And the worst part?

There’s no going back.

You can’t uninvent the ring light.

You can’t put the teeth back in the cocaine.

And you sure as hell can’t repackage sincerity once people stop buying it.

So what’s next?

Hell if I know. Maybe a return to muttering into typewriters in windowless rooms.

Maybe fire. Maybe silence.

But if you want a tip from a man who’s chased the ghost of America through barrooms, bunkers, and bureaucracies…

Buy stock in regret.

It’s about to be the only growth sector left.