EPISODE 7 MUSIC IN PHASE TIME

In the first sequence of Peter Brook’s film “Meetings With Remarkable Men,” tribes/clan people from miles around gather at the foot of a mountain range to observe a musicians challenge. The champion will not be the one who can play the fastest, or the longest piece, or the most difficult. Rather, the award will go to the performer who can make the mountains shake and shudder by the clarity, intensity, sentiment and purpose present in the music.

In our own time, the public musical inattentiveness has been cultivated progressively by a number of factors: Bubble gum pop music, the loudness wars, the excess of recordings available at one time in the internet, and the struggle among every type of media for the interest of the consumer.

Look around a digital music service for a popular song and you’ll likely find more than a few “tributes” to it — soundalike versions courtesy of faceless outfits with vague names.

It’s the musical equivalent of search-engine optimization manipulation — the equivalent to those websites that repurpose others outlets’ clickbait on their own, banner-ad-riddled webspace.

It’s a testament to the lousy way that music discovery exists in 2015. The search functions of the iTunes Store and Spotify and other digital-music services reward precise knowledge of what a listener might be searching for; there’s little opportunity for the sort of serendipity that would occur through, say, flipping through LP covers. The serendipity is precisely targeted, instead, and so what you get is a bunch of versions of something you’re already pegged to liking.

An individual has to bypass most of the Universal Soundtrack in order to function. The shared noise of conversation, laughing, crying, traffic, machinery, Muzak, nature sounds and broadcast media that surrounds scores of us, especially in the cities.

In our homes, our bodies hum along to our electrical appliances. Our instruments, dishwashers, — all of them run at 60 cycles per second helping us put another brick in our aural wall, we also shut the access to liminal consciousness that is empowered, indeed altered, by access to the deepest levels of musical expression.

According to New York Times critic Anthony Tommasini. “Virtuosos Becoming a Dime a Dozen“That a young pianist has come along who can seemingly play anything, and easily,” he notes, “is not the big deal it would have been a short time ago.”

Tommasini goes on to list several of the current super pianists who are able to leap over tall pieces like Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto and the Ligeti Etudes with a single bound. Apparently, the pianistic equivalent of breaking the four-minute mile or other sports record nowadays happens with such reliability that even teen piano students are at ease with such repertoire. The standar has become so punishing that the legendary Alfred Denis Cortot, remarks Tommasini, “would probably not be admitted to Juilliard now.”

Not So long ago, Vladimir Horowitz thrilled audiences with his groundbreaking interpretations of the piano repertoire. He even dared to re-write sections of pieces by Rachmaninoff, Mussorgsky and Chopin to “expand” them. Today, a pianist is not respected unless every note is just as the composer wrote it. No longer is musical self-expression, passion and perception valued above technical display — mainly because most listeners don’t know anymorer what to listen for.

‘The problem with some technically remarkable players is that they sometimes have nothing to say…’– the fastest double tongue, or the most impressive multiphonic, circular-breathing effects. Of course, this is assuming that composers have something expressive to say as well, beyond the latest circus effect or noise manipulation.

I’m not so sure Fritz Kreisler or Artur Rubenstein could come first at an audition or competition these days with all the technically flawless demands on musicians. People remember Rubenstein missing lots of notes, but always interpreting wonderfully!)

Then there’s cover bands. As the LA times puts it (…) The best tributes, like Led Zepagain, are carefully constructed and choreographed replicas of the bands they emulate. Some can even receive the respect of the artists they’re based on. The Musical Box has received endorsements from Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins and other members of Genesis. Members of the real Pink Floyd have appeared onstage with a tribute called the Australian Pink Floyd. In Los Angeles, Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger plucked Dave Brock from the Doors tribute Wild Child and made him their singer for four years.

With so many bands competing for gigs, the market is oversaturated. There are, no fewer than five Doors tributes plying their trade in Los Angeles: Wild Child, Break on Through, Peace Frog, Strange Days and Light My Fire. There’s a Cure tribute called The Cured and another called The Curse. There are even tributes to more recent artists such as The Killers and Steel Panther are now so popular that they have inspired their own tribute band. “They’re called Surreal Panther. They’re out of the U.K.,”

<>

Without doubt there are a lot worse ways to time than in perfecting one technique. It keeps one off the street out of the bars and social media. The devil will never get a hold of those un-idle hands and re-purpose them for trolling.

I don’t know if the focus on practice makes perfect is considered the easier path, and a infallible one at that. After all, if one is able to play a difficult piece immaculately, doesn’t that unconsciously make one unquestionably good? Not only that, but even an idiot can hear you and tell you’ve got chops.

But the truth is the sole function of practice is to enhance your ability to express yourself. It must be subservient to the art form whether it be music, painting, dance or writing.

The audience cannot be blamed for responding to what is often called “flash” — the player should be blamed for that. Those players who have opted for a flamboyant arrangement have not thought very deeply about their creative processes.

Picasso: ‘Art is the elimination of the unnecessary’

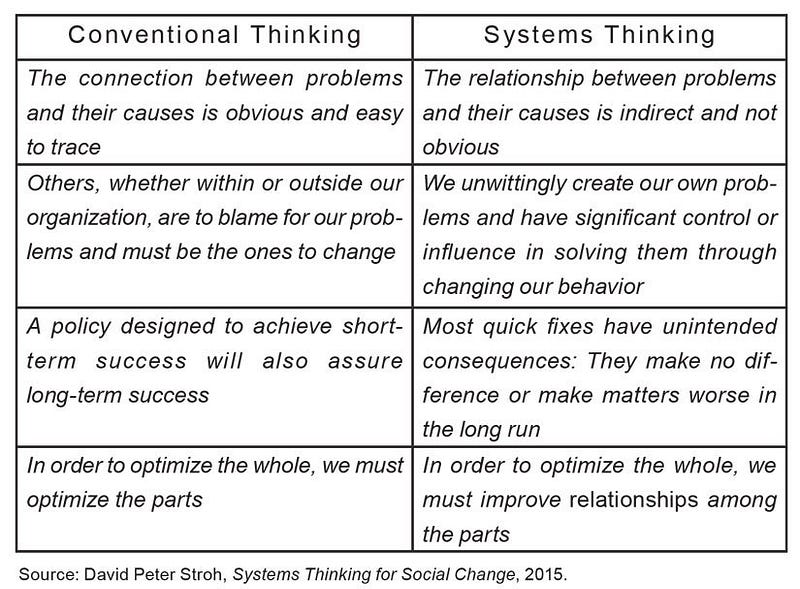

How do you measure the meaning of a phrase?

As a culture we deal with the measurable or the “metrics” as they are often called. The number of accurate notes per bar is measurable; how do you measure the understanding of a phrase’s meaning?

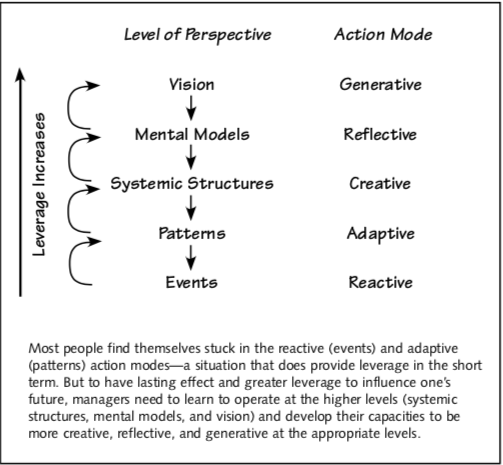

As a society we select for objectively measurable values and we get what we get. The problem that I am noticing in the modern milieu is that we seem to have been stranded on a on a version of reality that is killing us: we have replaced authentic playing (a fluid use of both “explore and discover mode” and “custom mode”) with a simulation of playing. A form of “custom mode” that represents itself as the totality of playing.

Simulated playing shows up as playing, takes itself as playing and, armed with a vast and often nuanced script of pre-defined signals and ‘suitable’ responses, even resembles playing. But it is not. It is custom, not learning. And, as a consequence, it is completely incapable of creatively responding to (changes in) actual reality.

Broadly speaking, we have become stuck in some sort of simulation and this is exceptionally hazardous. In fact, I’d like to encourage you to reflect on that this might be the fundamental problem of why we are in the situation we find ourselves in. Musicians today seem to be less adventurous in moving from one chord or note to another, instead following the paths well-trod by their predecessors and contemporaries,”

To be sure, a whole lot of the philosophy floating about these days is a muddle to say the least. And we will have to deal with that as well. But without real music, we can’t even really take the first step. We are ensnared using old apparatus promulgated by baby boomers to get to the bottom of how is it we have burnt most of cultural capital creating a simulation.

How did we get here?

A huge amount of early childhood is spent in discover/explore mode. Learning to walk, learning to talk, learning to pick up food and put it in your mouth. You can’t be taught any of this. You just have to use explore mode and learn it. Explore mode is largely to blame for all fundamental learning, for exploring your surroundings and forming novel insights and responses to that environment.

Here I quote Jordan Greenhall from his medium piece on thinking and simulated thinking

(…) But, and here is precisely where things start to go wrong, it is possible in some cases to move from “learning” to “being taught.” A classic is the good old multiplication table. Who among us “learned” multiplication? I don’t mean “used rote repetition to carve it as a deep custom,” I mean well and deeply came to grasp the fundamental essence of “to multiply” for yourself. My sense is that the answer is practically no-one (…)

If your only association with multiplication is the capacity to promptly answer questions like, “what is five times five” or “what is nine times nine,” you have turned multiplication into something that can be processed with custom mode. In the effort to accelerate and normalize the contents of mind, our society has chosen to apply “custom mode” to the multiplication table. That’s OK. And, in fact, maybe the only way to relate to the subject. It is an efficient way to do basic multiplication.

But it isn’t exploring discovering, And here is the dilemma: in society, it is often the case that most of the things that you need to be on familiar terms with were figured out a long time ago. You could re-experience them again for yourself, but for nearly everyone will tell you it is an exercise in ineffectiveness. Certainly this is not the sort of thing that a school striving to cram as much “comprehension” as possible into its students would go about doing.

(…)

Instead, the clever answer is to treat all knowledge as a version of the multiplication table: a sort of pre-fab script relating possible inputs (“three times three?”) and appropriate outputs (“nine!”). Who was the sixteenth President of the United States? What is the atomic weight of Hydrogen? What is the meaning of Walt Whitman’s self-contradiction? What is the appropriate relationship between individual liberty and common interests? (…)

Perceive possible inputs, scan available outputs, faithfully report on the most appropriate response. Quickly. Reliably. Speed and precision — the sort of thing that “custom mode” was designed for.

Do this long enough and your native capacities begin to atrophy. And in our modern environment, this is how we end up spending nearly all of our time.

Anyone who has played an instrument can almost feel the shift from learning to custom. For the first little bit, there is learning. You are exploring the shape and possibility of the instrument environment. But, and this is deeply crucial, no matter how complicated an instrument is, be it guitar, piano, banjo, violin, ukelele, it is ultimately no more than merely “complicated.” Unlike nature, which is basically “complex”, every instrument can be learned. After only a little while, you get a feel for how it works and then begin the process of turning it into custom. Into rapidly and competently running the right responses to the precise inputs. At a formal level, instruments precisely teach you to move as quickly as possible from learning to routine and then to maximally optimize practice.

When you look at how we really spend almost all of our time, it isn’t hard to see out how we got here. We are born discovering and exploring. And then we are immersed like Achilles in an environment that is constantly pushing us to optimize for simulated thinking.

This is deep problem at a basic level. But it is an even bigger problem at the cultural level. And under the contemporary trajectory of exponential technology, it is likely a disastrous predicament at the species level as These things are the glue that holds our society together

Simulated playing works.

For a while. In fact, as long as the frame of pre-fab patterns and responses that you carve into custom is actually adaptive to the real environment, simulated playing’s ability to quickly and reliably apply those responses can be really rather effective. For a while, it can make things pretty easy — and can superficially show up as a “golden age”. It’s no wonder that many young musicians are making the acquisition of technical perfection their number one goal — it has always been easier to go after the known as opposed to the unknown. We know how to get technique. We know what the notes are, now it’s a question of fingering, phrasing, articulation.

SUPERUNKNOWN

What is difficult is seeking the unknown. We don’t know what it is, so how can we look for it? More importantly, how can we listen for it? Because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of music, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones

Consider how real playing shows up to replicated playing. Rather than quickly and reliably returning the right results for the right inputs (like a good custom), playing begins awkwardly. Early on, playing will struggle to create anything at all. Simulated playing can dance and dazzle while playing is just figuring out how to walk.

Moreover, as it matures, the results of playing will look entirely unlike the “appropriate output” that simulated playing is expecting. As a consequence, for the most part, playing will show up as some combination of error, disability or bad attitude.

In fact, at a social level, playing will often show up as hostile. In a social environment largely conditioned by “role playing” identities that allow you to “fit in”, playing will be sending everything but the right signals. If you are not demonstrating good opinion and responding correctly to the right signals, you won’t show up as being part of the in group. And if you aren’t part of the in group, then you must be in the out group.

Simulated playing is limited to its pre-fab scripts. As a consequence, it doesn’t have good ways to respond to the novelties and subtleties of real playing. If it interprets playing as error, it might select a response of “dismiss” or “debunk.” If it interprets playing as hostile, it might select a response of “attack” or “defend”. Or scapegoat. Or witch hunt.

The more sophisticated the scripts, the more effectively simulated playing will be able to react to, limit and extinguish real playing. After all, it has the weight of almost the entire population on its side. To think in an environment infected with simulated playing is almost to invite a witch hunt.

A seeker is concerned first and foremost with expressing the content of the music on as deep a level as possible. Rather than an exclusive focal point on the linear flow of the notes, the depth of the content must be pulled out from underneath, as it were. The emotion and the turn of phrase cannot come from a linear, parallel conception, only from a straight down one. One must dig to find gold.

GOOD VIBRATIONS

In order to know what is currently unknown to one, it’s necessary to take the plunge into timelessness.

As long as we’re stuck in the revolving artificial moving parts , we can never be open to discover this territory. There exist out of the ordinary worlds, different universes, than those presented to us in daily life. These territories or realms are the sandboxes of scientists and mystics, who approach them from opposite directions but end up in the same place. The unexplained realms described by mandalas, poems, paintings, and mathematical equations have also, down through the ages, been explored by musicians. Indeed, it is only through music that many people will ever experience these realms.

The language of mathematics requires an understanding far beyond that of eighth grade algebra yet this thing called music cannot be expressed by words or theorems. The reality of music has much to do with the fact that sound is created through vibrations. The frequencies of the vibration are what give us the pitch but by limiting the perception and understanding of music solely to its surface sounds, most modern cultures have robbed music of its most vital element–the vibrational experience.

This is no mistake. Just as the understanding of pitch and melody has declined with successive generations the immensely satisfying sensation of feeling musical vibrations has been relegated to loud nightclubs and the speakers of passing cars. In such environments, with such music, there is little reason to seek the intricacies of melody, harmony, rhythm or other musical subtleties. Indeed, that’s not why anyone is there. Loudness comes at the expense of dynamic range — in very broad terms, when the whole song is loud, nothing within it stands out as being exclamatory or punchy. Indeed, it is found that the loudness of recorded music is increasing by about one decibel every eight years.

Grammy Award-winning percussionist Evelyn Glennie was compelled to train herself in the vibrational method of hearing, having gradually become deaf as a child. An essay on her Web site notes the following:

(…) Hearing is basically a specialized form of touch. Sound is simply vibrating air which the ear picks up and converts to electrical signals, which are then interpreted by the brain. The sense of hearing is not the only sense that can do this, touch can do this too. If you are standing by the road and a large truck goes by, do you hear or feel the vibration? The answer is both. With very low frequency vibration the ear starts becoming inefficient and the rest of the body’s sense of touch starts to take over. For some reason we tend to make a distinction between hearing a sound and feeling a vibration, in reality they are the same thing (…)

Music is the ripples in a stream. Melody is what stays in the brain, allowing us to recall the songs of childhood and youth. The here and now, however, is found in the vibrations. When one dives below the surface of a piece of music one can experience the trembling at its very source. But first one must be sensitive enough to know the source exists.

“Everything is vibrating, man!”

Vibration is how the soprano breaks the glass…it’s how the karate master smashes cement blocks…it’s how Joshua’s army took down the walls of Jericho and how John Henry beat the steam drill. Vibrations have the power to destroy, and therefore the power to create. Hence, a musician wields a mighty axe.

Some musicians seem to have an effortless understanding of the deepest vibrational intricacies — Miles Davis and Maria Callas come to mind as examples. The rest of us may have to work a little harder. Shall we throw out technique and custom playing, then, in search of that elusive musical magic? Absolutely not. We only need to remember — in the words of pianist and teacher Jimmy Amadie — “We play to express, not to impress.”

Contrast this scenario with the alternative path, that of the musical seeker. Such a musician does not shun acquiring technique but realizes that the music is the food, and the technique is the plate you serve it on. When the awesomeness of the plate starts to override the awesomeness of the food, can that be good for musical digestion?

‘We need to rediscover and redefine the function — the role — that music plays in our society’. The audiences are bored; the fast food we are offering them have been standardized just like those at the local Subway. You’re consuming high amounts of digital/digitized sounds. Consuming these insane amounts causes a buildup in your system, which can lead to perception problems. You’re consuming leftover and low quality ingredients You’re getting addicted to refined sugar and are known to be addictive. Those sandwiches are perfectly well and good, but who goes to Subway for an interesting or exciting meal?

By focusing on the message in the music — rather than how that message is transmitted — we can re-arrive at sincere communication, and experience the wealth of what the music has to offer, not to mention the wonderful differences that can exist among artists: there is excitement, passion, wildness, tenderness, sweetness, resilience, resolve — and on it goes. The possibilities are endless.