In recent years, there has been a growing concern about income inequality and the concentration of wealth among a small group of individuals in the United States. According to a report by the Institute for Policy Studies, the top 1% of Americans own more wealth than the bottom 90% combined. This concentration of wealth and power can lead to a situation where a few powerful elites control the market and limit economic opportunities for others.

The concept of scaling has become increasingly important in the modern business world, where companies seek to expand their operations and increase their reach. However, the act of scaling has its roots in the pre-capitalist era, characterized by feudal modes of production. This essay argues that scaling is not driven by any rational desire to preserve the capitalist mode of production but rather reflects a remnant of the pre-capitalist era.

There is no doubt that income inequality has been on the rise in the United States over the past few decades. According to data from the Congressional Budget Office, the top 1% of Americans saw their average after-tax income grow by 275% between 1979 and 2017, while the bottom 20% saw their average after-tax income grow by only 46%. This trend has contributed to the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small ruling class.

Furthermore, research has shown that there is a correlation between income inequality and limited economic mobility. A study by the Brookings Institution found that the United States has lower economic mobility than most other developed countries, with children from low-income families having less opportunity to move up the economic ladder than their counterparts in other countries.

Moreover, research has shown that market concentration has been on the rise in many sectors of the U.S. economy. A report by the Roosevelt Institute found that in many industries, a small number of firms control a large share of the market, leading to reduced competition and higher prices for consumers.

Scaling refers to the process of expanding a company’s operations and increasing its production capabilities. This can involve the acquisition of new resources, such as labor and capital, and the implementation of new technologies and processes. In the modern capitalist economy, scaling is often seen as a necessary step for companies to achieve growth and remain competitive.

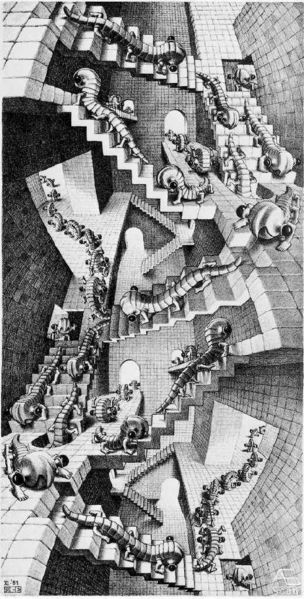

However, the roots of scaling can be traced back to the pre-capitalist era, characterized by feudal modes of production. Feudalism was a social and economic system in which landowners granted their subjects the use of land in exchange for their loyalty and service. The feudal system was characterized by limited economic mobility and a strict hierarchy of social classes.

Feudal modes of production refer to socio-economic systems in which the production and distribution of goods and services are controlled by a ruling class or elite. While many societies have moved away from feudalism and towards capitalism or other economic systems, there are still some examples of feudal modes of production in use today. Here are a few examples:

- Landlordism: In many parts of the world, particularly in developing countries, there are still wealthy landowners who control vast amounts of land and resources. These landlords often extract rent from tenants who work on the land, and may also control the distribution of water, minerals, and other resources.

- Sharecropping: Sharecropping is a system in which tenants work the land and share a portion of the profits with the landowner. This system is still used in some parts of the world, particularly in rural areas where land is scarce and access to credit is limited.

- Serfdom: Although officially abolished in many countries, there are still examples of modern-day serfdom, particularly in areas where there are high levels of poverty and limited access to education and employment opportunities. In some cases, workers may be forced to work in exchange for basic necessities like food and shelter, and may be unable to leave due to debt or other obligations.

- Caste systems: In some societies, particularly in South Asia, there are still caste systems in place that dictate a person’s social status and their ability to access certain resources and opportunities. These systems are often based on birth, and can be difficult to escape or challenge.

In this context, scaling was not motivated by any rational demand for the preservation of the capitalist mode of production. Rather, it reflected the desire of feudal lords to expand their power and influence by acquiring new land and resources. The feudal lords used their military power to conquer new territories and impose their rule over new subjects. This process of scaling allowed them to increase their wealth and status, and to consolidate their power over their subjects.

Feudal modes of production were most prevalent in Europe during the Middle Ages, but have largely been replaced by capitalist economies in the modern era. However, there are some examples of feudal modes of production that persist in the West today. Here are a few examples:

- Landlordism: While land ownership in the West is not necessarily tied to feudalism in the same way that it is in other parts of the world, there are still wealthy landowners who control large tracts of land and resources. For example, in the United States, large agricultural corporations often own vast amounts of land and exert significant control over rural communities.

- Traditional land tenure: In some parts of Europe, traditional land tenure systems still exist, particularly in remote or rural areas. These systems may involve hereditary land rights, with certain families or clans having exclusive control over certain parcels of land.

- Feudal remnants in law: In some countries, feudal remnants still exist in legal frameworks. For example, in the United Kingdom, there are still laws on the books that trace their origins back to feudal times, such as laws governing the ownership of mines and minerals.

- Patriarchal structures: While not strictly feudal, some scholars have argued that patriarchal structures in Western societies can be seen as a vestige of feudalism. These structures often privilege men over women, and can limit women’s access to resources and opportunities.

The emergence of capitalism in the 16th and 17th centuries brought about a radical transformation of the economic and social order. Capitalism was characterized by the emergence of a new class

While scaling can lead to a number of benefits, such as increased productivity and job creation, it can also contribute to the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few dominant players. Here are some ways in which scaling can lead to concentration:

- Economies of Scale: One of the key drivers of scaling is the pursuit of economies of scale, which refers to the reduction in cost per unit that occurs as a business expands its operations. As a company grows, it can often achieve cost savings through bulk purchasing, automation, and other efficiencies. This can lead to a competitive advantage over smaller firms, making it more difficult for them to compete and survive.

- Network Effects: Many industries exhibit network effects, which occur when the value of a product or service increases as more people use it. For example, a social media platform becomes more valuable as more people join and interact on the platform. This can create a winner-takes-all dynamic, where the dominant player captures most of the market share and profits, leaving little room for competitors.

- Barriers to Entry: As dominant players grow larger and more powerful, they can use their resources to create barriers to entry for new competitors. This can take the form of exclusive contracts with suppliers, intellectual property rights, or regulatory capture. This makes it more difficult for new entrants to enter the market and compete.

- Mergers and Acquisitions: As companies grow and become dominant players, they may seek to consolidate their power through mergers and acquisitions. This can further concentrate market power in the hands of a few dominant players, making it even more difficult for smaller firms to compete.

- The gig economy, which is characterized by short-term or freelance work arrangements, has been the subject of much debate and critique in recent years. One argument that has been made is that the gig economy is feudal in nature, and that it perpetuates many of the same dynamics of power and control that were present in medieval feudal systems.

Firstly, it is argued that the gig economy is characterized by a lack of stable employment or income security, which can leave workers vulnerable to exploitation by employers. This is reminiscent of the feudal system, in which serfs were tied to the land and subject to the whims of their lord or master.

In addition, many gig economy workers are subject to a rating system in which their performance is evaluated by customers or clients. This can create a power dynamic in which workers are subject to the whims of those who control access to work opportunities. Similarly, in the feudal system, the lord had complete control over the lives of their subjects, including their access to resources and employment opportunities.

Furthermore, the gig economy can be seen as a form of modern-day sharecropping. Many workers are not paid a fixed wage, but rather are compensated based on the amount of work they are able to complete. This can create a situation in which workers are essentially renting access to the means of production (in this case, their own labor), and are subject to the control of those who own or control the platform through which they find work.

Finally, the gig economy is characterized by a lack of collective bargaining power or worker protections, which can leave workers vulnerable to exploitation by employers. This is similar to the feudal system, in which serfs had little or no say in the decisions that affected their lives.

In conclusion, while the gig economy may differ in many ways from the feudal systems of the past, there are certainly some similarities in terms of the power dynamics and control mechanisms that are present. As we continue to debate the merits and drawbacks of the gig economy, it is important to consider these historical parallels and work to ensure that workers are protected and empowered in this new economic landscape.

In summary, while scaling can lead to many benefits, it can also contribute to the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few dominant players. As companies become larger and more powerful, they can use their resources to create barriers to entry for new competitors, consolidate their power through mergers and acquisitions, and take advantage of network effects to capture most of the market share and profits. This can lead to a concentration of wealth and power that can be difficult to overcome.

As companies grow larger and more successful, they often become more dominant in their respective markets, which can create barriers to entry for new competitors and limit consumer choice.

Furthermore, as companies grow and become more powerful, they may begin to engage in practices that can be seen as reminiscent of feudal or imperial taylorism projects. For example, they may rely on traditional land tenure systems or other forms of control over natural resources in order to maintain their dominance. They may also engage in exploitative labor practices, such as using sharecropping or other forms of indentured servitude, to keep labor costs low and maximize profits.

These types of practices can be seen as a form of modern-day feudalism, in which a powerful elite controls the means of production and exerts control over the labor force. Similarly, they can be seen as imperialistic, in that they involve the exploitation of resources and labor from less powerful regions or countries.