Twenty years ago, licensing a rock song in a TV commercial would be met with immediate cries of “sell out.” But within the last decade, commercial syncs are providing an additional source of income as record sales continue to slump — so it’s no surprise that the number of classic rock songs in advertisements has increased. As AC/DC (whose music is now in an Applebee’s commercial) once pointed out, “Money Talks.”

Songs carry emotional information and some transport us back to a poignant time, place or event in our lives. It’s no wonder a corporation would want to hitch a ride on the spell these songs cast and encourage you to buy soft drinks, underwear or automobiles while you’re in the trance.

Tom Waits

Think of Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” in a Cruise Ad a song about heroin (the mother of all addictive drugs) which opens with a William S. Burroughs reference as a fitting song to sell family cruise trips. Even if you miss the heroin-specific references (including the cringe-inducing “Of course I’ve had it in the ear before”), there’s the repeated “Liquor and drugs” line — which Royal Caribbean turned into “looks so good” when they tapped the tune for a series of commercials.

The Western canon’s aura makes it just the thing for pitching luxury brands like the Lincoln Motor Company, whose 2017 holiday ad unfolded over a track of Shostakovich’s swoony Waltz №2. GNR’s breakout hit “Welcome to the Jungle” is a harrowing warning about Los Angeles to newcomers,(“If you got the money honey we got your disease”) and selling your soul to make it (“you can taste the bright lights but you won’t get there for free”). At least, that’s what it was about in 1987. In 2016, it’s about Taco Bell’s quesalupa.

Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son” in a Jeans Commercial

Like Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In the U.S.A.” and Ronald Reagan, the true meaning behind John Fogerty’s “Fortunate Son”was a biting critique about the privilege and hypocrisy of rabidly patriotic politicians for a denim ad. The fact that they axed most of the lyrics (lines prescient of George W. Bush’s adult life) but kept the “oooo that red, white and blue!” part showed that Wrangler was either willfully ignoring the song’s real message.

Then you have Viva Las Vegas” by Elvis Presley vs. Viagra. An Elvis classic ruined for the rest of your natural life and Mercedes-Benz” by Janis Joplin vs. Mercedes-Benz with the car execs hitching a ride to the point on Janis’ satirical take on materialism.

What we see here is how Capital uses music to carry out its teleogicla purpose utilizing music a sort of stand-in for this late stage capitalism. These advertisements can sometimes be funny, and often even move (that David Bowie’s “Starman” Super Bowl).

REIFICATION

Of all the terms that have arisen to explain the impact of capitalism, none is more vivid or readily grasped than “reification”-the process of transforming men and women into objects, things. The principle of reification, emerging from Marx’s account of commodity fetishism, provides an unrivaled method for understanding the real effects of capital’s impact on consciousness itself.

Our point is that contemporary perceptions of sense and reality have been reified, and that esthetics can express why this is the case, with major consequences for understanding the role of music. If you can harness the trappings of a style — taking its surface level idioms and cliches, while deliberately leaving behind any emotional authenticity to be a backing track that helps someone sell something, you’re probably half the way there.

Reification signs are proliferating around us-from the branding of products and services to ethnic and sexual stereotypes, all manifestations of religious faith, the rise of nationalism, and recent concepts such as ‘spin’ and ‘globalization.’

Reification is a process where an abstract concept is turned into something concrete or tangible. In the context of music, reification can refer to turning an art form into a commodity that can be bought and sold. Licensing is the process of granting permission to use intellectual property, such as music, in exchange for a fee. While licensing has its benefits, it has also led to the reification of music, where artists are forced to create music that can be easily licensed and sold rather than creating music that is true to their art form.

The rise of licensing can be traced back to the 1960s, when the music industry realized the commercial potential of music. Music became a commodity that could be marketed and sold, and record labels saw the opportunity to make money by licensing their music for use in films, TV shows, and commercials. This led to a change in the way music was created, with many artists and record labels focusing on creating music that could be easily licensed and sold.

The reification of music led to the homogenization of the rock and roll genre, where all the music sounded the same. Record labels were more interested in creating music that could be easily licensed rather than music that was true to the art form. This led to the decline of rock and roll, as people lost interest in the genre that had once captured their hearts.

Another way licensing killed rock and roll was through the commercialization of music. Record labels and artists were more interested in creating music that could be easily licensed and sold rather than creating music that had artistic value. This led to the rise of manufactured bands, where record labels would put together a group of people who looked good together and could sing, and market them as a band. These manufactured bands had no artistic value and were only created to make money through licensing and merchandising.

Yes, that is one of the consequences of reification. When an abstract concept, like music or art, is transformed into a tangible commodity that can be bought and sold, it loses some of its original meaning and becomes associated with materialistic values, such as consumerism, status, and profit. This transformation can be detrimental to the authenticity and creativity of the art form, as it is now driven by commercial interests rather than artistic expression.

SIGNIFIER, SIGNIFIED, SIGN

Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys vs. Sunkist

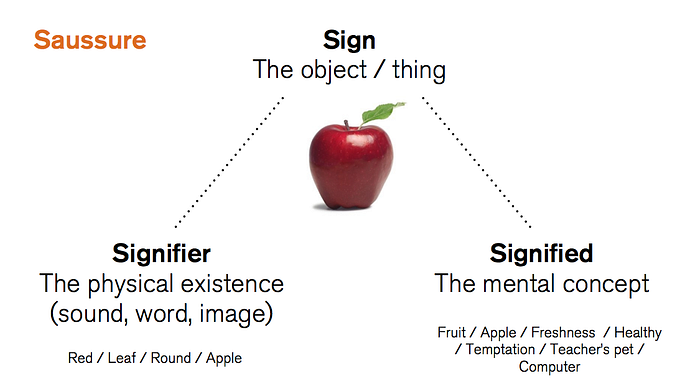

The 1966 “pocket symphony” by Brian Wilson cost a record-breaking $50,000, along with his health. It went on to market a carbonated orange beverage. According to Swiss linguist and semiotician Ferdinand de Saussure, there are two main parts to any sign:

- Signifier: This connotes any material thing that is signified, be it an object, words on a page, or an image.

- Signified: The concept which the signifier refers to. This would be the meaning that is drawn by the receiver of the sign.

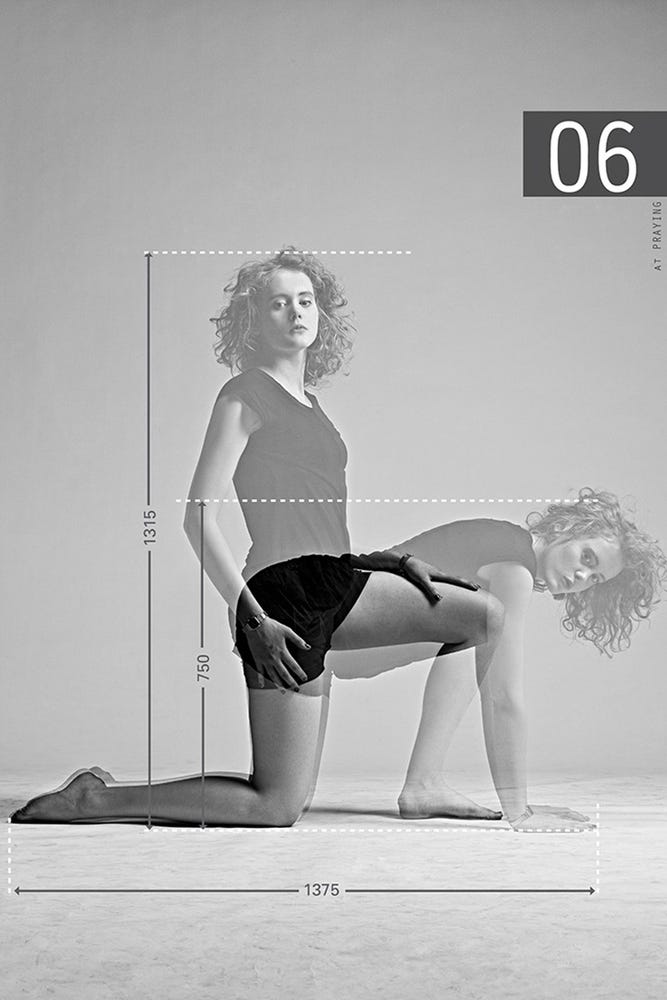

The example below shows how this can be understood.

A great example of effective use of semiotics is found in the use of metaphors. These commonly understood concepts tend to resonate easily with your target audiences. For example, “a glass half full” is perceived as a sign of optimism and positiveness.

In 1978, the original “Good Vibrations,” sung by the Beach Boys, was used to introduce consumers to “The Sunkist Soda Taste Sensation.” In 1981, Sunkist Orange Soda became one of the ten best selling carbonated soft drinks in the United States. Today, the tradition continues; Sunkist and Diet Sunkist, sold by Cadbury Schweppes Americas Beverages.

For this ad, a strong message is effectively communicated without the use of much words.

Music is different to the spoken language in many ways, but possibly the most important way is that it can communicate without pointing to something in the real world or having a precise meaning. In other words, it has a degree of non-conceptuality.

Reification is the mental process of transforming the non-concrete into something concrete, a ‘fact.’ The US national anthem will be a perfect example of a reified piece of music. And by explaining this reified music we say first of all that its meaning is solidified:

The mind does not go off on an interpretive journey when we hear it — this music means USA. Consider for example the popular use of the anthem at Woodstock in 1969 by Jimmy Hendrix, generally viewed (probably incorrectly) as an act of anti-war sentiment. This interpretation was possible only because there was no doubt what the melody meant-it wasn’t an ad lib set of notes, like a free jazz solo, it was the national anthem-something that was identifiable.

Let’s focus for a second on words. Think about what happens when you talk for a minute. Words denote different things and provide us with a shortcut to convey information. If we combine words to explain something, we create a very unsatisfactory depiction of nature. Consider of the difference between asking you what it’s like to be in a car accident, or kissing someone, versus the real reality of being in a car crash or kissing someone. Actual experience is almost nothing like hearing a first-hand account.

One of the reasons for this is because spoken language is itself reified — used to construct an approximation of experience — to work around the limitations of our senses and leaving out a whole world of information in doing so. Worse still, there are more than likely facets of knowledge we are not yet in a position to understand or interact.

Music is often thought to have a stronger link with the non-conceptual for a few reasons. It can provoke vague and difficult to define emotions. It can exist without communicating anything specific. It can mean different things to different people. In fact, many say that the allure of music is that you can say things with it that you never could with spoken language.

So, if you’re wondering where I’m going with this — here it is. A shorthand description: When music is reified, it behaves a lot more like a spoken language. It means something specific. It can be described easily. It is unable to change because its meaning (or for semiotics people, its signifier) is fixed. The melody of the US National anthem doesn’t require me to engage with the non-conceptual. I know what it is.

So one good way of telling whether a piece of music is overly reified or not is if you’re able to describe it easily in words. They have all in different ways become a thing. A known musical object. This is of concern to composers because we recognise the value of the abstract nature of music, which allows us to communicate in a way that the spoken language is often unable to do.

If you have problems wrapping your head around this how the iconic banjo duel scene in the movie ‘Deliverance’ caused a powerful association with his instrument that has overpowered how audiences listen to it ever since.

In this case, it’s not any particular melody or song that’s reified but the instrument itself and it’s also worth noting that it’s happening against the musician’s will. In the example of the banjo — it is no longer free to communicate musically — instead becoming a humorous shorthand for backwardness. And the US national anthem represents its country so strongly that it can’t be mistaken for anything else. In all these examples, interpretation is resisted and the music is unable to change.

There are so many other ways that music can be reified: rules for example can lead to reification — for example the idea that chorus must always follow verse or that the opening movement of a symphony must use sonata form.

Over-reliance on rules or patterns may create repetitive musical artifacts that do not engage the listener but merely remind them of what they’ve heard before. Especially in music, lyrics are a kind of reification by people like Taylor Swift who use them to convey to the listener what they should feel, in case they turn their brains on to perceive meaning for more than five seconds.