1. All’s Well That Ends Well (1602) Based on the ninth tale of the third day in Giovanni Boccaccio’s masterpiece, the Decameron. Completed in 1353, the Decameron is a collection of one hundred short stories told by friends over ten days during the Black Death.

William Shakespeare is widely regarded as one of the greatest playwrights in history, and his plays have had an enduring impact on literature and culture. One of his lesser-known plays, All’s Well That Ends Well, has its roots in the Decameron, a collection of stories by the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio. In this essay, we will explore the precursor to All’s Well That Ends Well and how it influenced Shakespeare’s play.

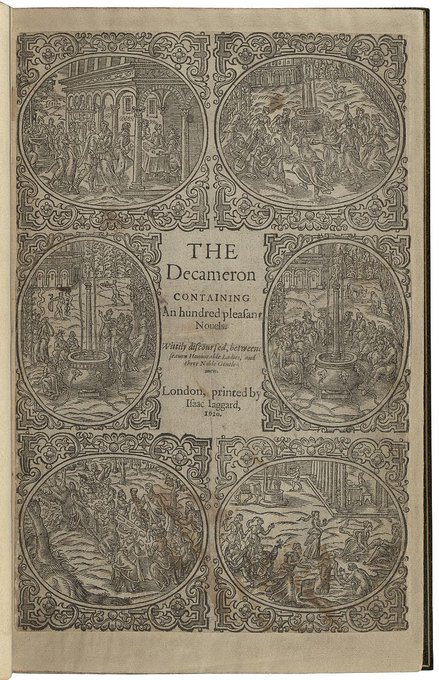

All’s Well That Ends Well was first performed in 1602 and is based on the ninth tale of the third day in Boccaccio’s Decameron. Completed in 1353, the Decameron is a collection of one hundred short stories told by friends over ten days during the Black Death. The ninth tale of the third day is the story of Giletta di Narbona, a young woman who falls in love with Bertram, a nobleman who does not reciprocate her feelings. Giletta is determined to win Bertram’s love and goes to great lengths to do so, including using a healing potion to cure the King of France, who in turn grants her the right to marry any man of her choosing. Giletta chooses Bertram, who flees to Florence to avoid the marriage. Giletta follows him and ultimately succeeds in winning his love and devotion.

Shakespeare’s play follows the same basic plot, but with some significant differences. In All’s Well That Ends Well, the protagonist is Helena, a physician’s daughter who is in love with Bertram, the son of a Countess. Bertram is sent to the French court to serve the King, and Helena follows him, using her medical skills to cure the King’s illness. In return, the King promises her anything she desires, and she chooses Bertram as her husband. Bertram, however, is not interested in marrying Helena and flees to Italy. Helena follows him and, with the help of a bed trick, manages to conceive a child with him, which ultimately leads to their reconciliation.

One of the key differences between Boccaccio’s story and Shakespeare’s play is the character of Giletta/Helena. In Boccaccio’s story, Giletta is a resourceful and determined woman who uses her intelligence and skill to win Bertram’s love. In Shakespeare’s play, Helena is more passive and relies on tricks and subterfuge to achieve her goals. This change reflects the patriarchal society in which Shakespeare was writing, where women were often seen as weaker and less capable than men.

Another significant difference is the addition of the bed trick in Shakespeare’s play. This device, which involves a woman disguising herself as another woman to sleep with a man, is a common motif in Renaissance literature, and Shakespeare uses it to great effect in All’s Well That Ends Well. The bed trick is a reflection of the idea that women are not in control of their own bodies and that men can use them for their own purposes.

In conclusion, All’s Well That Ends Well is based on the ninth tale of the third day in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, a collection of short stories told during the Black Death. Shakespeare’s play follows the same basic plot as Boccaccio’s story, but with some significant changes that reflect the patriarchal society in which he was writing. The addition of the bed trick and the character of Helena, who is more passive than Giletta, are examples of how Shakespeare adapted the original story to suit the cultural and social norms of his time. Despite these differences, All’s Well That Ends Well remains a compelling and entertaining play that continues to be performed and enjoyed today.