Using the word “fascism,” even ironically, is a high-risk, low-reward strategy. It is not a trivialization of historical evil but a precise metaphor for absolute, inflexible authority.

The word “fascism” is used here with intentional, tongue-in-cheek irony. The four-track machine was the opposite of actual fascism—it was a constraint that enabled rather than oppressed; it forced innovation rather than conformity.

It’s “fascism” only in the sense that the machine said “NO” with absolute authority: “No, you cannot have five tracks. No, you cannot undo that reduction mix.” But this tyrannical inflexibility paradoxically created the conditions for unprecedented creative freedom. The “authoritarian” tape machine liberated the Beatles; our “libertarian democratic” DAWs often imprison us in a bottomless supermarket aisle of choice.

The Architecture of Constraint: The Violence of Choice

Forget the geodesic domes. Forget the brutalist concrete. The most radical design template of the 1960s was a magnetic tape ribbon exactly two inches wide.

It had four tracks. Four. That’s all you got. That was the box. The cage.

And inside that cage, they built cathedrals.

You wanna know why the Beatles still sound like a signal from a sharper, more vivid planet? It’s not magic. It’s not even just talent. It’s a brutal, brilliant workaround born of sheer, pig-headed material constraint.

Here’s the ugly truth your streaming-service algorithm will never understand: they had to choose. They had to commit.

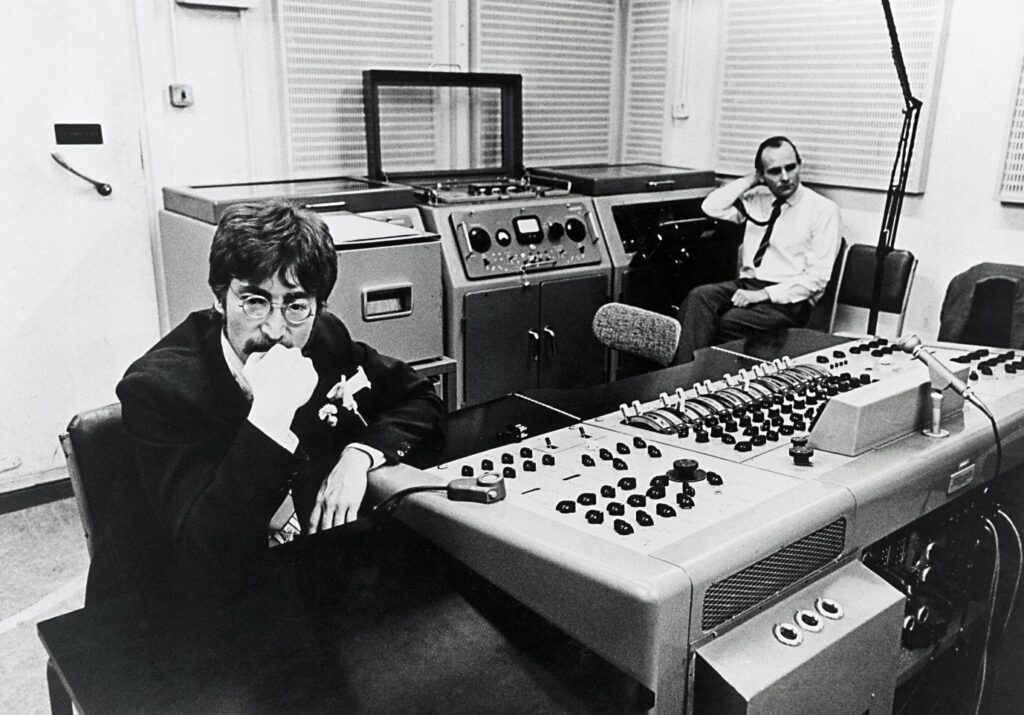

Picture Abbey Road, 1966. Four young guys standing around a machine that cost more than most people’s houses, staring at four parallel lines of magnetic oxide. Four channels. Four chances. Four slots in the sonic matrix.

They’d lay down the bedrock—rhythm track, bass, maybe a scratch vocal—on three tracks. The foundation of the temple. But here’s where it gets beautiful and terrifying: that foundation was temporary. A scaffolding to be demolished.

Then came the moment of creative violence: the Reduction Mix. The Bounce.

They’d squash those three tracks down, permanently, onto one single track of a brand new tape. They were burning their bridges. Literally erasing the past to invent the future. That mixed-down track was now a single, monolithic object. The bass level was now stone. The drum sound was now law. Ringo’s snare hit? Frozen in magnetic amber forever. No going back.

Each element existed in its own sovereign state on the tape because it had to. It had earned its slot.

Think about that for a second. In our age of infinite undo, of 128-track digital workstations, of “we’ll fix it in post,” these mad scientists were making irreversible decisions in real-time. They were committing acts of creative terrorism against their own work, destroying the multitrack evidence of their process to make room for the next assault.

This isn’t nostalgia. It’s systems design. Look at any credible list of the 500 greatest albums ever made. The overwhelming majority weren’t just recorded in the past; they were recorded within a specific technological window—from the 4-track era through the early 16-track era of the early 70s. This was no accident. It was the Architectural Age of music, a sweet spot where technology imposed constraints that forced to think on your feet or off your feet, what ever rocks your boat.

They had to choose. They had to commit.

And in the glorious, empty silence of those three newly-cleared tracks? That’s where the phantoms lived.

One track for the lead vocal, often doubled—that iconic, in-your-face, hyper-present sound that cuts through your skull like a laser. Another for the harmonies, those celestial gang chants, those impossible three-part weaves that sound like aliens singing human emotions. A third for the secret weapon: the piccolo trumpet on “Penny Lane,” the sitar wail on “Norwegian Wood,” the orchestral freakout on “A Day in the Life,” the ring of a cash register on “Money.”

That’s the secret sauce, the DNA of their sound. It’s not that Lennon’s voice is louder. It’s that it has nowhere else to be. It exists in its own sovereign state, on its own dedicated piece of the tape. It isn’t fighting the snare drum for bandwidth. The snare drum was already chiseled into the monolith, its place settled forever.

This is the antithesis of the modern “unlimited tracks” paradigm. There’s no “we’ll fix it in the mix.” The mix already happened. It was a strategic decision that paved the way for the next assault.

Here’s what the machine understood: the four-track wasn’t just a recording system—it was a *decision-forcing system*. Every choice had weight because every choice had cost. The system’s apparent limitations were actually its core feature set. 1.The Necessity of Pre-Production: You had to arrange the song before you recorded it. You had to know how many instruments would fit on the limited tracks. This forced composition and arrangement to be considered as a single, holistic entity. The song and its recording were inseparable.

2. The Band as an Organism: With only 4 or 8 tracks, you often had to record musicians playing together in a room. This captured not just notes, but a performance—the human interplay, the slight fluctuations, the energy of people creating together in real-time. The bleed between microphones wasn’t a problem to be eliminated; it was the glue that held the recording together.

3. The Scarcity of Overdubs: Every overdub was a precious event. A string section, a horn section, a backup vocal—these weren’t afterthoughts. They were major production decisions that had to be planned for and earned their place. This scarcity is why the saxophone solo on a Springsteen record or the string swell on a soul ballad feels so powerful. It wasn’t one of 50 elements; it was the element.

The Tyranny of Abundance

Fast-forward to today. Your nephew’s bedroom setup has more tracks than the entire Abbey Road facility. He’s got virtual instruments that would make George Martin weep. Unlimited overdubs. Pitch correction. Time stretching. The ability to record 847 guitar parts and choose the best one later.

And what does he make? Sonic porridge. Digital soup. Music that sounds like it was mixed by committee and mastered by algorithm.

On the surface, DAWs democratized music-making: anyone with a laptop could record an album. But the counterintuitive effect is that by flooding the space with infinite options, the DAW often collapsed imagination into templates: quantized beats, loop libraries, presets. Instead of more possible futures for music, we often got fewer—iterations on the same grid.

Jobs lost? Sure—engineers, tape ops, session players, mid-tier studios.

But possibilities lost? That’s deeper—whole musical pathways that never formed because the tools nudged us toward the convenient, the repeatable, the frictionless.

It’s a cultural version of what economists call opportunity cost: not just what was destroyed, but what never got a chance to exist.

* Modern Music’s “Mush” Problem is Multi-Causal: Blaming only unlimited tracks for forgettable music ignores other massive factors: the economics of streaming, changes in listening habits, the decline of the album format, and homogenization by corporate algorithms. The technology is one factor in a complex system.

Because here’s the thing about unlimited resources: they breed unlimited indecision. When you can do anything, you do everything. When every choice can be unmade, no choice has weight.

This is textbook technological pathology. The nephew’s setup exhibits a fundamental dysfunction: stated purpose versus actual purpose. The stated purpose is making music. The actual system purpose has become managing infinite options. The system has grown to serve itself rather than its supposed goal.

The Beatles operated under the opposite philosophy—imposed functional constraint. Every element that made the final cut had to justify its existence. Had to earn its slot on the precious tape. It was Darwinian selection applied to magnetic particles.

You want that backwards guitar solo on “I’m Only Sleeping”? Better be worth it, because once it’s on there, it’s married to whatever else is sharing that track. You want strings on “Yesterday”? They get one track, and Paul’s vocal gets another, and that’s the ecosystem. Learn to love it.

The Sound of Commitment

This wasn’t just a technical limitation. It was a philosophical framework. A aesthetic constraint that shaped not just how the music sounded, but how it was conceived.

Listen to “Tomorrow Never Knows.” That’s not a song built track by track. That’s a sonic architecture planned from the ground up. Every element locked into place with the precision of a Swiss watch. The backwards guitars, the tape loops, the compressed drums, Lennon’s vocal floating in that weird vocal booth limbo—all of it existing in perfect, unchangeable relationship to everything else.

They couldn’t move the bass drum two clicks to the right in the final mix. They couldn’t bring up the backing vocals just a hair. Those decisions were made in the moment of creation, burned into the magnetic substrate like cuneiform in clay tablets.

And that commitment, that finality, that’s what gives the music its weight. Its presence. Its reality.

What the engineers understood: systems with irreversible states—but in service of the goal rather than opposing it.

The Engineering Lesson for the Digital Barbarians

Now here’s where it gets interesting for you technical barbarians paying attention. What we’re witnessing is a fundamental truth about how things actually work: complex systems that function have *always* evolved from simple systems that functioned. The four-track didn’t just work—it forced work. It was a system whose limitations became its core functionality.

Modern DAWs? They’re complex systems designed from scratch that violate every principle of robust design. They promise infinite possibility and deliver infinite paralysis. The more sophisticated the recording system becomes, the more it fights against its own stated purpose of making music.

So next time you fire up your DAW with its infinite tracks and its unlimited undo, remember the four-track fascists of Abbey Road. Remember the creative violence of the reduction mix. Remember what it sounds like when artists are forced to choose, when every sonic real estate decision matters, when the mix isn’t something that happens later—it’s something that happens now, in this moment, with these exact elements, forever.

This is engineering 101: artificial constraints that serve the system’s true purpose. The four-track was a *forcing function*—it made good decisions inevitable and bad decisions impossible.

Set yourself some limits. Four tracks. Maybe eight if you’re feeling generous. Force yourself to commit. Make the choice. Burn the bridge. Mix it down. Build systems that constrain you into excellence rather than enable you into mediocrity.

Build your cathedral inside the cage.

Because constraint isn’t the enemy of creativity—it’s creativity’s secret weapon. It’s the thing that turns infinite possibility into actual art. It’s what engineers call “productive system resistance”—when the system pushes back in exactly the right way.

The Beatles knew this. The tape knew this. The machine knew this. The engineers know this.

Now you know it too.

*The future is four tracks wide.*

Leave a Reply