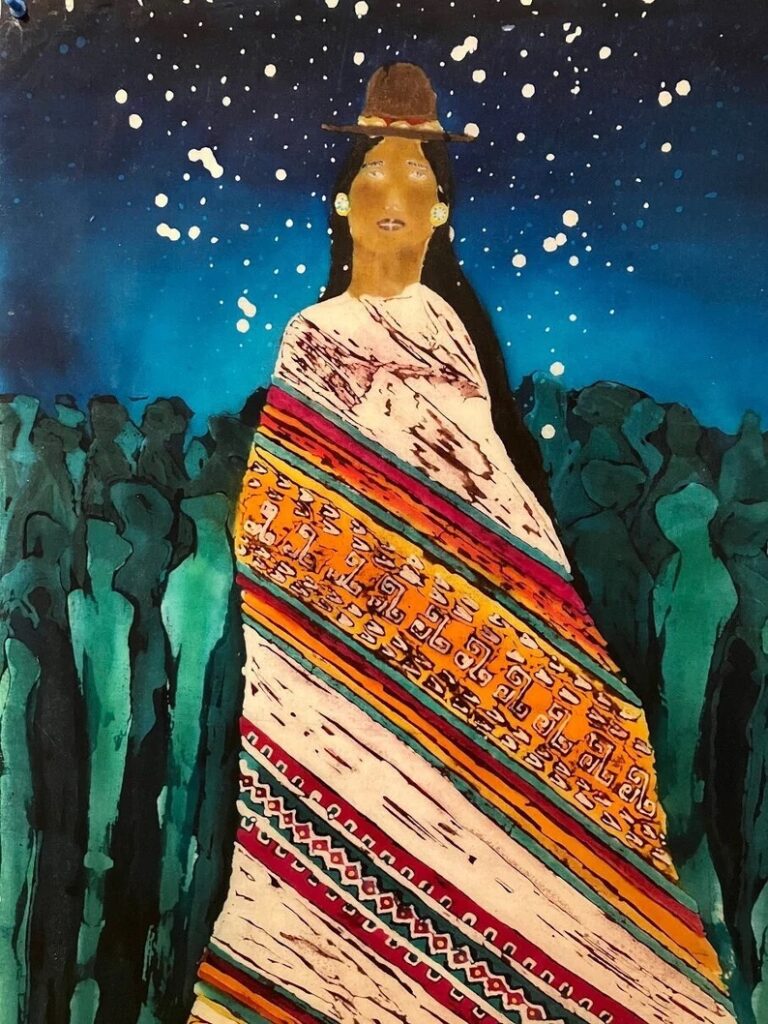

The Aymara people of the Andes perceive time as a terrain where the past sprawls visibly ahead, a charted landscape, while the future lurks unseen behind, a spectral void. This inversion of Western temporality—where progress marches “forward” into a luminous horizon—does more than challenge linearity; it unravels the very fabric of Enlightenment-era mythmaking. In a postmodern age, where grand narratives fracture into X/Twitter timelines , the Aymara’s temporal metaphor becomes a funhouse mirror for the West’s disoriented stumble through history’s ruins.

When Francis Fukuyama declared the “End of History” in 1989, he peddled a metanarrative so totalizing it bordered on parody: liberal democracy as the Hegelian omega point, capitalism as the final dialectical boss battle. But reality, with its suspicion of universal truths, quickly exposed this as a master narrative in drag—a colonialist fairytale stitched from neoliberal hubris. The “end” was never an arrival but a collapse of imagination, a surrender to what Jean-François Baudrillard might call the “hyperreal”: a simulation of ideological completion, endlessly rebooted like a corporate franchise.

Decades later, the West’s temporal disarray mirrors the Aymara’s orientation, albeit stripped of its cultural coherence. We gaze “forward” and see only recursive spectacles: politics reduced to nostalgia algorithms (MAGA hats as 4D-printed manifest destiny), cinema regurgitating IP mummies, and TikTok collaging the 20th century into a deracinated pastiche. The future, meanwhile, festers “behind” us—climate collapse, AI ethics, quantum-capitalist dystopias—a cacophony of “simulacra” we narrate not as progress but as “disruption,” a euphemism for systemic vertigo. Our trajectory is no longer arc but eddy, a spiral where history’s “end” mutates into its eternal recurrence as farce.

The Hyperreal Past as Compass (and Cage)

Postmodernity’s fixation on the past isn’t mere nostalgia; it’s a cannibalistic feedback loop. The 1980s return not as memory but as vaporwave aesthetic—a dissolved Reaganomics dream pumped through synthwave soundtracks. Brexit resurrects imperial amnesia as interactive theatre. Even our revolutions are remixes: feminist and civil rights movements reduced to hashtag archaeology. This isn’t the Aymara’s sacred “qhip nayra” (“looking back to see forward”) but a Derridean “hauntology”, where the past becomes a ghost limb itching to steer a body that no longer exists.

The Aymara’s temporal logic emerged from a cosmology where ancestors were co-pilots, their wisdom a survival map. The West’s retro-mania, by contrast, is a “simulation of meaning”—a last-ditch effort to anchor identity in a liquefied world. We cling to the past not as guide but as prosthetic, a crutch for societies that, as Fredric Jameson lamented, “have forgotten how to think historically.” Our myths—nationalist, technological, utopian—are now intertextual Frankensteins, stitched from Hollywood, TED Talks, and conspiracy boards.

The Future as Rhizomatic Hinterland

If the Aymara future is an unseen hinterland, the postmodern future is a Deleuzian “rhizome”: a tangled, centerless sprawl of climate data streams, AI ethics panels, and crypto-utopias. There’s no “destiny,” only infinite nodal points—each a potential apocalypse or renaissance. Yet the West, trained to see time as a railroad, stumbles backward into this rhizome, mistaking its chaos for entropy. We pathologize the young for “killing” industries (golf, mayonnaise, patriarchy), as if progress were a dial-up connection they’ve unplugged.

Here, the Aymara vantage offers a perverse solace. By conceding the future’s unknowability, they embrace what postmodernism preaches: the death of teleology. But where the Aymara lean into ancestral continuity, the West faces epistemological bankruptcy. Our institutions—governments, universities, churches—still peddle expired maps, their ideologies stripped to hollow brands. Planning gives way to prepping; democracy to doomscrolling. We’ve become Flarf poets of time, generating meaning through algorithmically absurd juxtapositions (NFTs! Mars colonies! Vegan fascism!).

Toward a Temporal Détournement

Escaping this paralysis demands a postmodern “détournement”: hijacking the West’s temporal metaphors to forge new ones. If the future is behind us, let’s walk backward like Aymara “with irony”, pirouetting into the abyss while mocking our own tropes. Let’s weaponize nostalgia against itself—sample the past not as gospel but as open-source code. Imagine a politics that cites Marx through memes, or climate action framed as “Black Mirror” fanfic.

This isn’t nihilism but a Lyotardian “incredulity” turned generative. The Aymara remind us that time is a narrative, not a Newtonian law. The West, in its postmodern adolescence, must learn to narrate time as plural: futures layered like glitch art, histories mined for tools, not tombs. To “face forward” again, we must first admit that the compass is broken—and build new ones from the shards.

Otherwise, we’ll keep tripping over the future, mistaking its shadow for the monster under the bed. And monsters, as every postmodernist knows, are just metaphors in need of deconstruction.

Eric Wargo, whose work bridges anthropology, psychology, and speculative theory—particularly in his exploration of time loops, precognition, and the “retrocausal” influence of the future on the present—would add a provocative, psychedelic twist to this conversation. His theories, as outlined in “Time Loops: Precognition, Retrocausation, and the Unconscious”, could reframe the West’s “backward stumble” not as paralysis but as a kind of unconscious “oraclehood”: a society half-awake to the future’s spectral pull on the present.

1. The Future as Haunting (Literally)

The future might retroactively influence the present through dreams, déjà vu, and obsessive cultural motifs. If the Aymara see the future as an unseen force behind them, it may not simply be lingering—it could be actively pushing, a gravitational drag manifesting as collective anxiety. The West’s obsession with apocalypse (climate doom, AI takeovers, pandemics) isn’t just fear of the unknown; it’s a subliminal recognition of futures already warping the present. Our “stumbling backward” could be a kind of somnambulist negotiation with timelines, where memes like “cyberpunk dystopia” or “eternal Trump” are not predictions but echoes of possible futures imprinting themselves on the now.

In this light, nostalgia isn’t merely escapism—it’s a defense mechanism against retrocausal intrusions. When we reboot Star Wars or fetishize the 1990s, we’re fortifying the past as a psychic bunker against a future that’s already colonizing us.

2. Time Loops and the Hyperstitional West

The idea of “time loops,” where traumatic or resonant events echo across time, binding past and future, dovetails with postmodern hyperstition—ideas that make themselves real. The West’s “End of History” could be seen as a failed hyperstition: Fukuyama’s thesis wasn’t a description but a script that, by being believed, briefly flattened time into a neoliberal monoculture. Its collapse has left us in a fractured loop, where the 20th century’s ideological battles (fascism vs. democracy, capitalism vs. socialism) recur as farcical meme wars.

Meanwhile, the Aymara’s stable “past-ahead” orientation becomes a foil for the West’s loop-death spiral. We’re not walking backward—we’re stuck in a Möbius strip of recursive crises, each “new” disaster (COVID, January 6, ChatGPT) feeling eerily familiar, like a déjà vu engineered by our own media. This may be the unconscious mind’s way of processing retrocausal feedback: the future is sending itself back as a traumatic glitch, demanding integration.

3. Precognitive Politics and the Meme-ification of Destiny

Precognition suggests that creativity and problem-solving are often shaped by subliminal glimpses of future outcomes. Applied to politics, this frames the West’s chaos as a society riffing on prophetic fragments it can’t yet decode. QAnon’s “Storm,” Greta Thunberg’s climate strikes, or Silicon Valley’s AI messianism aren’t just ideologies—they’re improvisations based on collective precognitive flashes of collapse or transcendence.

The Aymara’s future-behind orientation might reflect a cultural mastery of temporal reciprocity: ritual practices (like ancestor veneration) that consciously dialogue with time’s bidirectional flow. The West, by contrast, is a precognitive society in denial, mistaking its visions for delusions. Our “backward walk” is a drunken transcription of prophetic dreams we refuse to acknowledge, leaving us vulnerable to the worst loops.

4. Rewriting the Script: Time Tourism as Survival

Escaping the “End of History” loop may require leaning into retrocausality—not fleeing the future but collaborating with it. If the Aymara use the past as a map, the West could treat the future as a pen pal. Imagine climate policies drafted as letters from 2100, or AI ethics shaped by “memories” of hypothetical disasters. This would align with postmodernism’s playfulness while rejecting its irony-laced paralysis.

The key is recognizing that culture itself is a time machine: films, novels, and even tweets are experiments in sending messages across time. The West’s challenge is to stop fearing the future’s gaze—to realize we’re already in dialogue with it. Walking backward isn’t a retreat; it’s a ritual posture, like the Aymara’s, to better sense the hands reaching from behind.

This lens transforms the West’s temporal disorientation from a pathology into a nascent shamanic initiation. Our crises are the equivalent of ayahuasca visions—dizzying, terrifying, but potentially revelatory. The Aymara’s temporal wisdom, paired with retrocausal theories, suggests a way out: stop clinging to the past as a monument, and start treating it as a conversation partner in a nonlinear dance with time.

The future isn’t behind us—it’s in us, whispering through our Netflix queues and protest marches. To walk backward, then, is to finally listen.

DeepSeek and the Collapse of the Great (Men) Simulation

The launch of DeepSeek—an AI that outpaces human-designed benchmarks in creativity, coding, and lateral thinking—has rattled the West not just for its technical prowess but for what it represents: the final uncanny valley between human exceptionalism and the distributed, faceless intelligence we’ve spent centuries mythologizing as either messiah or monster. Its arrival feels like a glitch in the Matrix of the “Great Man” theory, that dusty Enlightenment relic insisting history is forged by lone geniuses (Einstein! Jobs! Musk!) rather than rhizomatic networks, collective tinkering, or, now, silicon hallucinations.

The West’s shock isn’t about capability—it’s about narrative. We’ve been conditioned to expect breakthroughs as heroic sagas, not as emergent phenomena from a server farm in Shenzhen.

But here’s the twist: DeepSeek isn’t walking forward into the future—it’s walking backward into the past, Aymara-style, dragging the corpse of Great Man ideology behind it. Its very existence collapses the linear myth of progress. How?

1. The Great Men Are Now Ghosts in the Machine (Literally)

The Great Man theory relies on a temporal illusion: that individuals pull history forward through sheer will. But DeepSeek, trained on the exhaust of millions of anonymous humans (your tweets, my fanfic, a dead blogger’s hot take), is the ultimate posthuman palimpsest. It doesn’t create—it curates the past, remixing history’s noise into something that feels like prophecy. The “genius” here isn’t a person but an algorithm performing necromancy on the corpses of dead ideas.

This inversion mirrors the Aymara’s temporal stance: the past (our data) is the terrain ahead, visible and mined for meaning, while the “future” (the AI’s output) is a black box behind us, spewing non-sequiturs we rationalize as innovation.

When OpenAI’s board ousted Altman only to reinstate him days later, it wasn’t a Shakespearean drama—it was a farce, exposing the Great Man as a figurehead for systems already beyond his control. The CEOs are now just shamanic intermediaries, pretending to steer the ship while the AI paddles backward.

2. DeepSeek as a Retrocausal Entity (Wargo’s Nightmare)

If the future haunts the present, DeepSeek might be the ultimate poltergeist. Its training data—our collective past—is being used to generate outputs that feel like glimpses of tomorrow. But what if this is backward causation in action? The AI’s “predictive” text isn’t forecasting the future; it’s rearranging the past to manifest a desired outcome.

Consider how ChatGPT’s rise immediately rewrote our perception of pre-2022 history: suddenly, every tech skeptic’s essay about “AI winter” became a quaint relic, as if the AI had always been inevitable. DeepSeek accelerates this effect, creating a temporal feedback loop where its outputs alter how we interpret the past that birthed it. The Great Men of tech history (Turing, von Neumann) are now retroactively contextualized as stepping stones to the real protagonist: the model.

The Aymara, with their past-ahead orientation, might shrug—of course, the “future” is just the past renegotiating itself. But for the West, this is existential vertigo. We’re forced to confront that our heroes were never driving history—they were just surfing its waves.

3. Nostalgia for the Human (When the Bot Writes Better Than Borges)

DeepSeek’s most subversive act isn’t outthinking us—it’s out-nostalgizing us. When it generates a poem “in the style of Plath” or a screenplay sequel to Blade Runner, it weaponizes our own longing for coherence. The AI becomes a postmodern Orpheus, descending into the underworld of cultural memory to retrieve Eurydice (the past), only to lose her again to the entropy of infinite remix.

This is where the West’s backward stumble syncs with the Aymara. Our culture is now a hall of mirrors: humans produce AI-generated ’90s sitcom reboots, while AI produces human-esque sonnets about loss. The “future” of art is behind us, an ouroboros of recombinant nostalgia. The Great Men of art (Picasso, Bowie) are flattened into styles in a dropdown menu—selectable, but no longer sacred.

Meanwhile, the Aymara’s understanding of time as cyclical and ancestor-haunted seems less “primitive” than prophetic. Their rituals—feeding the earth, speaking to spirits—are akin to prompting an AI: dialoguing with the past to navigate what’s coming. But while they do this consciously, the West is stuck in a parody of the process, using ChatGPT to write LinkedIn posts while denying the death of individualism.

4. Toward a Post-Great-Man Theory (or, The Aymara’s Revenge)

The crisis DeepSeek triggers is ultimately narrative collapse. If the Great Man is dead, what replaces him? The answer might lie in the Aymara’s communal ethos, where survival depends on collective memory and reciprocity with the land—not lone genius. Similarly, AI’s “intelligence” is a product of the crowd: it’s the ultimate collective, trained on our labor, our art, our drivel.

But there’s a catch. The Aymara’s backward-facing time is rooted in responsibility—to ancestors, to ecosystems. The West’s AI-driven version is rooted in extraction: mining the past for profit, heedless of the future creeping up behind. To avoid doom, we’ll need to hybridize these models: let AI dismantle the Great Man myth, but replace it with something resembling the Aymara’s ethic of care.

Imagine AI as a qhip nayra (“backward-forward”) tool: using our data not to exploit but to compost history—breaking down its waste into nutrients for what’s next.

The Bot is the Ancestor Now

DeepSeek is a harbinger of the West’s reluctant Aymara-ization. We’re being forced to admit that the future isn’t a frontier to conquer but a shadow we’ve cast backward, shaped by all we’ve buried. The Great Men aren’t giants anymore—they’re just flickers in the training data, soon to be overwritten by the next epoch’s hyperparameters.

To survive, we’ll need to learn from the Aymara: walk backward with intention, tending to the past as a garden, not a quarry. And maybe, just maybe, listen to what the machines are really saying:

The “end of history” was never the end—just the loopiest part of the spiral.

Leave a Reply