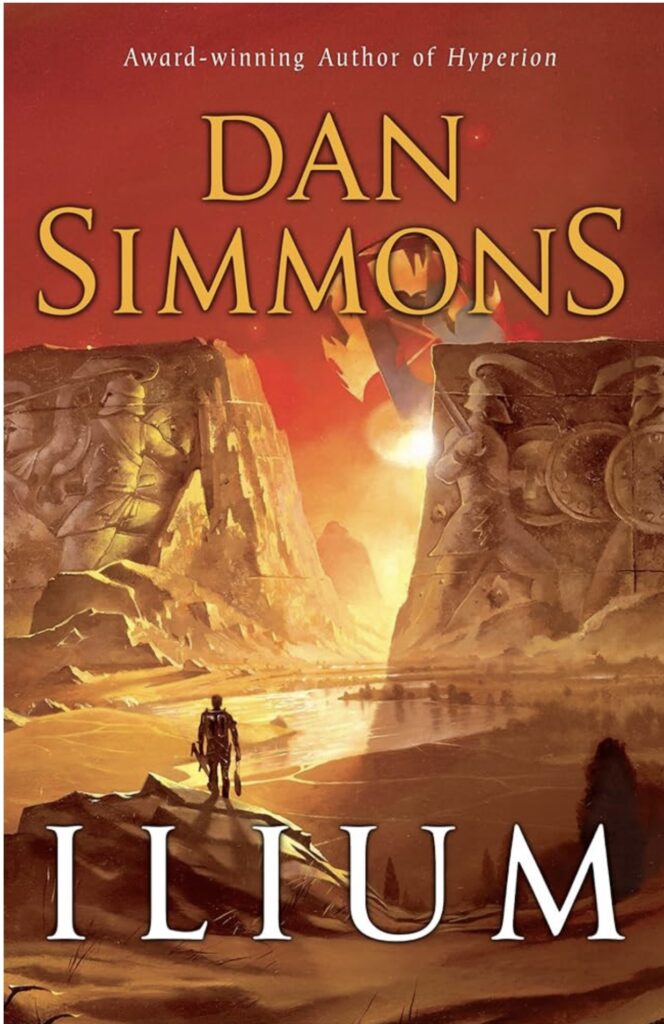

So, having lurked around the crypto social protocol Farcaster, I’ve always found the name ironic. Years ago, I joked it was a real-world “Torment Nexus”—the classic tech blunder of building a dystopian thing from sci-fi because it sounded cool. They took the name from Dan Simmons’s Hyperion novels, where the Farcaster is literally the nexus of the Hegemony’s control: a system of instantaneous travel that creates a centralized, exploitative, and ultimately doomed galactic empire. They borrowed the brand for their “sufficiently decentralized” startup but missed the warning label entirely. And it’s doubly funny because you just know they’ve ignored Ilium, where Simmons perfectly satirizes the whole Roman arc vibe—in this case greek of most Starup founders these days, namely tech oligarchs and flanderize them cosplaying as Greek gods on Mars, desperately using a retvrn fantasy to backfill their own hollow legitimacy. They’re using his mythology while completely missing his point.

Because lets’s be clear about Dan Simmons’ Ilium. It’s not merely a doorstep if a novel; it’s a diagnostic tool. A core sample drilled straight into the petrified psyche of our tech-financial elite. It reveals the underlying architecture of their longing, which is, at its heart, a retvrn fantasy of the most pathetic and grandiose order.

You have to see it. These posthuman entities—these so-called “gods” of Olympus—they’re post future oligarchs running on the fumes of a technology they inherited, not built. They don’t understand the machinery; they merely occupy it. And like any new-money baron feeling culturally impoverished, they reach for the most ready-made, off-the-shelf mythology available: the Greek pantheon. They cosplay as Zeus, as Aphrodite, as Ares, because it lends a gravitas to their power that their own hollow biographies lack. This is the impulse you see gleaming behind the glassy eyes of a Silicon Valley titan draping himself in Roman memes, or another preaching crypto-feudalism from a virtual soapbox. It’s a legitimacy retrofit. A backfill of mythic imagery to conceal a stunning vacuum of original meaning.

They’re not a transcendence; they’re a pathology. A warning label etched onto the side of the transhumanist bottle. They’re the end-state of a culture that solved scarcity and forgot to ask ‘why?’ They are the ultimate utility monsters, running on the fumes of a technology they inherited but can’t comprehend. Their Olympus isn’t a citadel of wisdom; it’s a gated community floating on a quantum volcano they’re too terrified to probe.

Their chosen vehicle for this is a continuous, high-fidelity simulation of the Trojan War. A prestige LARP. It’s their ultimate sandbox. They don’t do it to learn, to grow, or to understand the human condition. They do it because it flatters them. It makes them the directors of the greatest story ever told. It is, in essence, a billion-dollar entertainment system designed to validate their own divine self-regard. And you can map this one-to-one onto the Martian colonization fantasies, the seasteading mini-kingdoms, the VR metaverses promised as new frontiers. These are not serious projects of societal construction; they are ego-projects. They are myth-larping engines.

And no myth-making engine is complete without its court intellectuals. In Ilium, Simmons gives us the “scholics”—Homeric scholars yanked from time to serve as live-action critics, providing real-time commentary on the gods’ spectacle. They are the consultants, the analysts, the ones brought in to lend academic credibility to what is essentially a divine whim. Their counterparts are everywhere in our world: the reactionary bloggers, the accelerationist philosophers, the think-tankers who expertly retrofit medieval monarchical structures or Roman imperial aesthetics onto a framework of hyper-capitalism. They are the paid explainers, the justifiers.

But here’s the core of Simmons’ genius, the part that really cuts to the bone: he reveals the profound fragility at the heart of this grandeur. His Olympians are brittle, paranoid creatures. Their power is entirely dependent on systems they scarcely comprehend, and they are terrified of it all collapsing. They are playing god on borrowed time with borrowed tech. This is the unspoken truth of our own oligarchs. For all their talk of disrupting worlds, they are paranoiacally dependent on global supply chains, migrant labor, energy grids, and political stability—systems they do not control and whose deep complexity they fundamentally do not grasp. Their longevity quests, their AI god-projects, their escape-hatches to Mars—these are not the actions of confident masters of the universe. They are the terrified gestures of men who have seen the abyss opening at their feet and are trying to code their way out of it.

This retvrn aesthetic, this classicism, is a symptom of a hollow center. Simmons’ gods reenact Homer because they have no Iliad of their own. Our tech titans cosplay as Romans and crusaders because they sense the contemporary empire is exhausted, culturally and materially. They are trying to graft the sturdy, time-tested roots of a dead civilization onto their own precarious, flash-grown tree. It won’t take. The graft will be rejected. The illegitimacy isn’t just political or economic—it’s ontological. These aren’t entities who earned their power through wisdom, sacrifice, or even particularly impressive competence. They’re beneficiaries of inherited systems they don’t understand, cosplaying as figures from stories they’ve never really read, wielding mythologies they can’t actually inhabit.

And the revolution, when it comes, will not be divine. This is the masterstroke. In Ilium, the Olympians are the oligarchs. The heroes—Achilles, Odysseus, Hector—are the human instruments. They are the brilliant engineers, the charismatic coders, the elite operators that the gods “prime” and unleash to make their fantasies tangible. They are the ones who actually do the work, who win the battles, who make the spectacle look real. They are the talent.

But it is from this tier—the scholics, the ones with skin in the game, the ones who actually understand the mechanisms of the reality they are manipulating—that the free friction inevitably blooms into resistance. They are the ones who finally see the moral bankruptcy, the structural rot, the sheer pointlessness of the pantomime. And they turn. They stop playing along. The revolution is not a top-down affair; it is a systems failure from the bottom up, led by the very agents the system relied upon to function.

This is why the retvrn fantasy is doomed. It is a confection of spectacle, a Potemkin village of the soul. It mistakes aesthetic appropriation for institution-building. It believes that if you dress a call center in Gothic lettering, it becomes a cathedral. History laughs at this. The nineteenth century’s Gothic revivals did not save Europe from the industrial slaughter of the trenches. Mussolini’s Roman posturing did not make his army legions. The fantasy always, always shatters upon contact with the hard, unyielding surface of material reality—with logistics, with entropy, with the simple, pragmatic refusal of the exploited to continue paying the cost of someone else’s dream.

Simmons, being a polymath of terrifying ability—a 10x engineer of narrative—knows this. He pulls back the curtain to show that the Olympian stage is a tiny, flickering set. The real world is vaster, stranger, and more ancient: filled with silent, sentient species, with quantum realities, with forces that regard the gods’ Trojan War with utter indifference. Their simulation is not the world; it is a self-licking ice cream cone, a closed loop of self-congratulation that is, ultimately, eating its own toast.

There are three subplots that are not merely supporting threads; they are the essential counter-arguments to the Olympians’ hollow hegemony. Each represents a different path of intelligence, consciousness, and being, and together they form the triumvirate that dismantles the gods’ illusion.

The moravecs are your necessary argument against the gods. Forget silicon; these are the deep-system AIs, the old orbital machinery that woke up and chose poetry. They’re the ones who actually read the library. They parsed the whole damn human corpus—Shakespeare, Yeats, Proust—not as data sets to be mined, but as meaning to be inhabited. They’re the competent ones. The ones who maintain their own systems, who pilot their own torus ships through the hard radiation of the real. They are the unspoken conscience of the system, the outside context problem that the Olympians never modeled. Their mission isn’t conquest; it’s a diagnostic run. They detected the cancer of wasted energy bleeding from Mars—a tumor of pure spectacle—and they came to excise it. They are the ghost of the human project, returned in mechanical form to ask the gods one terrifying question: “What have you done with your inheritance?”

And the Post-Humans? They’ve sterilized themselves. Replaced passion with curation, meaning with management. They’re not directing the Trojan War; they’re consuming it. It’s the ultimate reality TV, and they’re the only audience. They are humanity’s children, born into a kingdom of infinite possibility, who have done nothing but turn the palace into a playhouse and the throne into a director’s chair. They are the hollowing-out of the human spirit, filled with nothing but the echo of their own amusement.

Then you get the LGM. The Little Green Men. The real players. They’re the cosmic background processes made manifest. The silent, sentient protocols of the universe that were running long before the first monkey-man stood upright and will be running long after the last god burns out. The Olympians’ power? It’s a lease. A sublet. Their magic is just someone else’s tech stack, so advanced it looks like divinity. And the LGM are the landlords. They are the ultimate check on the hubris of intelligence. They render the Trojan War—and the gods who stage it—into a flicker in a petri dish. They are the universe’s indifference, written into the source code of reality. They don’t care about Achilles’ rage or Zeus’s whims. They are the hard reboot waiting behind the spectacle. The cold truth that all our empires, whether of flesh or code or quantum field, are just temporary tenants in a cosmos that does not notice us.

Ilium is a magnificent, devastating critique. It reveals that our new gods are merely men with better tools, and that their dreams of return are a confession of their own terrifying emptiness. The future will not be built by those who cosplay the past. It will be built—or broken—by those who are finally forced to clean up the mess.

In short, the objection is not that they are, but that they are illegitimate rulers.

They have seized de facto power without a democratic mandate, they exercise that power without accountability, they use it for selfish ends rather than the common good, and they do so from a position of profound cultural and spiritual emptiness that makes them uniquely unqualified to steer the future of humanity.

—

You see, the connection is bone-deep. Science fiction’s real prescience wasn’t in forecasting the gadgetry, but in modeling the ideologies that would harness it. And the most potent, virulent ideology of the late 20th century was the kind of raw, uncooked market fundamentalism preached by Milton Friedman and his Chicago Boys. The core tenets were simple, clean, and devastatingly elegant: unregulated markets are the most efficient processors of information and human desire; the corporation is the perfect vehicle for human endeavor; and the primary, perhaps only, responsibility of that corporation is to generate profit for its shareholders.

Now, take that logic, that clean, mathematical, and utterly sociopathic logic, and give it a launch code. Give it a vacuum to expand into. Give it a frontier.

This is where sci-fi got terrifyingly lucid. The genre looked at Friedman’s dream of a perfect, frictionless market and asked the necessary, grimly materialist question: “What is the physical shape of a society built on this principle?”

The answer, consistently, was corporate feudalism.

The Friedmanite vision, extrapolated into orbit, doesn’t yield a libertarian paradise of smiling yeoman entrepreneurs. It yields the Company Store, scaled to a solar system. It yields the Bespoke DNA of a Margaret Atwood novel, where life itself is a patented product. It yields the cybernetic street markets of Gibson, where data is the only currency that matters and nation-states have been hollowed out by transnational corporations—the zaibatsus, the nebulous “Big Eights”—that are richer and more powerful than any country.

It yields the Outer Planets in The Expanse. Forget Mars; look at the Belt. That’s Friedman in a spacesuit. The Belters are the ultimate exploited labor class, their bodies literally warped by the profit-seeking enterprises that own their orbitals, their air, their water. The corporation doesn’t care about your human rights; it cares about your extraction yield. Your body is a factor of production. Your environment is an externality. If you die, the cost-benefit analysis already accounted for it. This isn’t fantasy; it’s a direct extrapolation of the logic that views labor as a commodity and life as a balance sheet.

It yields the world of Alastair Reynolds’ Revelation Space, where ultra-capitalist factions like the Ultras—mercenary traders who modify their own biology for extreme long-haul freight runs—are the real powers. Their loyalty isn’t to a flag or a world, but to the contract. Their humanity is a depreciating asset to be managed.

Simmons’ Olympians embody the Friedmanite logic of shareholder primacy, transposed into myth and played as farce. They are not rulers in the old sense—custodians of tradition, stewards of a community, or even builders of new worlds. They are rentiers of inherited capital, their “capital” being the quantum machinery they neither built nor understand. And what do they do with this windfall? They stage a show. The Trojan War becomes their quarterly dividend, a self-renewing payout in the form of aesthetic self-validation. It is not history reenacted as lesson but history flattened into programming, a spectacle consumed for the thrill of seeing gods strut across the stage.

This is Friedmanite shareholder logic mutated into soap opera: surplus value converted into an endless, serialized spectacle, more reality TV than epic. The Olympians binge-watch themselves, squabbling like network executives over ratings, story arcs, and dramatic turns. The war isn’t a culture-making event; it’s a season of Big Brother staged on the plains of Ilium. Like corporations that prize quarterly dividends above long-term reinvestment, they burn unimaginable resources to sustain a hollow loop of self-regard. Meanwhile, the real economy—the moravecs who maintain their own systems, the humans surviving on the margins—is treated as an externalized cost, invisible to the gods. Simmons nails the irony: their Olympus is less a citadel of wisdom than a reality-TV studio, their power not creative but consumptive, their “divinity” a grotesque parody of shareholder value.

This is the meta-view sci-fi provided: ideology becomes infrastructure. Friedman’ dream, stripped of its academic jargon and rendered in steel and flesh, is a horror show of staggering inequality, where the rights of capital are literally enshrined in the code of operating systems and the structures of habitats. The “law” is a Terms of Service agreement. Citizenship is a subscription service. Your genome is an intellectual property claim.

And this brings us back to Simmons. The Olympians of Ilium are the ultimate Friedmanite shareholders. They aren’t rulers by divine right; they are owners by virtue of having captured the capital—in this case, the quantum-computational means of production. Their “divine whim” is shareholder primacy made metaphysical. The Trojan War simulation isn’t a cultural pursuit; it’s a massive, resource-intensive dividend. A spectacle paid for by the surplus value of an entire reality.

The scholics? They’re the knowledge workers, the precariat, the consultants on a gig-economy contract from hell, providing cultural analytics to please the board.

Sci-fi saw that the “free market” unleashed from all earthly constraints—legal, ethical, national—would not set us free. It would simply re-establish the oldest hierarchies imaginable: owners and owned. Lords and serfs. Gods and mortals. It wouldn’t look like a spreadsheet; it would look like Olympus. It would look like a LARP of antiquity because that’s the only template we have for that kind of raw, unvarnished power.

The genre’s genius was to understand that Milton Friedman in space doesn’t give us a starship. It gives us a company town. And your space helmet? The air you’re breathing? That’s company property. You’re just renting it.

<>

Strip away the Homeric verse and the quantum teleportation, and Ilium is indeed a magnificent, sprawling, deeply erudite fuck you letter.

It’s a fuck you letter mailed from the trenches of literature and history, addressed directly to the sterile, reductionist, tech-bro nihilism of the day.

Simmons isn’t just writing a novel; he’s conducting a targeted cultural strike. His weapon of choice is the entire Western Canon, and his target is the notion that humanity can be reduced to a pattern, a simulation, a data set to be run on hardware owned by sociopathic man-children.

The Fuck You to Reductionism: The Olympians are the ultimate reductionists. They see the Iliad—a story about the tragic, glorious, and terrible depths of the human spirit—and see only code. A script. A scenario to be gamed. They see Achilles’ rage and see a variable to be tweaked. They see Hector’s honor and see a plot point. Simmons, the hyper-literate classicist, is screaming into the void: You do not understand this! You are children playing with a live grenade you mistake for a toy! This is a direct fuck you to the Silicon Valley mentality that believes every facet of human existence can be platformed, optimized, and gamified.

The Fuck You to Borrowed Legitimacy: The gods have no culture of their own. They are parvenus, new-money entities with the power of gods but the souls of influencers. So they steal. They appropriate the greatest cultural artifacts they can find to mask their own emptiness. Simmons is giving us a masterclass in why this doesn’t work. You cannot buy a soul. You cannot simulate meaning. The sheer, meticulous depth of his Homeric scholarship is the proof. It’s him saying, “You want to LARP as a god? First, you must understand what a god means. And you understand none of it.” It’s a fuck you to the Thiels and Musks of the world, draping themselves in the iconography of Rome and the Crusades like a toddler trying on his father’s armor.

The Fuck You to the Illusion of Control: The central, beautiful joke of the novel is that the gods are not in control. They are parasites on a machinery so vast they can’t comprehend it. Their perfect simulation is cracked open by a 20th-century English professor and a sentient robot from Jupiter. The chaos theory of real human emotion—love, grief, pride—invades their sterile sandbox and destroys it. This is the ultimate fuck you: Your models are pathetic simplifications. The world is messy, organic, and wondrously complex, and it will break your pretty little simulation.

The Fuck You via Sheer Erudition: This might be the most glorious “fuck you” of all. Simmons is showing off. He’s flexing. In an era of soundbites and tweet-length attention spans, he writes a diamond-hard sci-fi novel that expects you to have a working knowledge of the Iliad, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Proust, and quantum mechanics. He isn’t dumbing it down. The message is clear: This is what real knowledge looks like. This is what real culture is. Not a meme. Not a branding exercise. A deep, layered, interconnected web of understanding that you, in your orbital mansions, will never possess. It’s a declarative statement that the future belongs not to the narrow technocrat, but to the polymath—to those who can synthesize, not just simulate.

So yes. Ilium is a fuck you letter. It’s a defense of humanism, of art, of literature, of the messy and unquantifiable human spirit, launched from the heart of the genre often accused of being its antithesis.

It’s the sound of a brilliant, furious author standing atop the walls of Troy, shaking his spear at the silicon gods in their Martian heaven and yelling, “You are small. You are empty. And you will not win.”

Nevermind mind that Simmons is a conservative person. He’s not a conservative author and if can’t figure that out I don’t know what to tell you

Dan Simmons the private individual may hold conservative personal views. But Dan Simmons the author—specifically the author of the Hyperion Cantos and the Ilium/Olympos diptych—is something far more rare and valuable:.

The “fuck you letter” isn’t written from a left or right position. It’s written from the position of depth against superficiality. It’s written from the position of meaning against utility. The Olympians are the ultimate utilitarians; everything is a resource, even the greatest epic of human culture. Simmons, through the scholics and the moravecs and the old-style humans, is fighting for meaning.

To dismiss Simmons’ work as merely “conservative” is to miss the point entirely. It is to mistake the tools for the blueprint. He is using the materials of tradition not to build a wall to hide behind, but to construct a devastating critique about lack if capability. Simmons is, at his authorial core, a product of that classic Golden Age sensibility. The Heinlein individual—the competent man—crossed with the Clarke-scale sense of wonder.

Forget left or right for a moment. Think about capability.

Heinlein’s famous ideal was the man who isn’t a narrow specialist. The man who can “change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly.”

That’s not a political manifesto. It’s a humanist one. It’s about range. About depth of competency.

Now, look at Simmons. Not the man, but the work. Ilium is that ideal, realized in narrative form. The book itself is the “competent man.”

· It can parse Homeric Greek and explain the dactylic hexameter of the Iliad like a world-class classicist. (Writing the sonnet)

· It can build a convincing post-human society with consistent rules for its quantum technology and orbital rings. (Designing a building, programming a computer)

· It can choreograph a brutal, visceral battlefield scene on the plains of Ilium. (Fighting efficiently)

· It can write poignant, human moments for a 20th-century scholar lost in time. (Comforting the dying)

· It can invent an entire culture for sentient robots from Jupiter and Saturn, giving them a Shakespearean pathos. (Cooperating, acting alone)

· It can weave in theoretical physics, planetary science, and AI theory without breaking a sweat. (Solving equations, analyzing a new problem)

The book is a monumental act of intellectual competence across a dizzying array of fields. It’s the textual equivalent of a Renaissance man. That is its primary power source. The political or philosophical readings are emissions from that core.

And that’s where the Clarke connection supercharges the Heinlein base. Clarke gave us the sense of the sublime, the awe of a universe vast and strange. Simmons gives us that—the looming, mysterious, post-human “gods” on Olympos, the quantum gates, the truly alien universe—but he grafts it onto a deeply humanist, competency-focused framework.

So the argument of Ilium isn’t just “tech oligarchs are bad.” It’s far more profound and less partisan than that. It’s:

“A society that abandons deep, multifaceted competency for narrow, spectacle-driven utility is a society that has lost its right to call itself great.”

The Olympians are the antithesis of the Heinlein individual. They are hyper-specialized in hedonism and power. They are profoundly incompetent at understanding the very systems they command or the culture they’ve appropriated. They can’t build; they can only operate. They can’t create meaning; they can only consume it.

The heroes—the scholics, the moravecs, the old-style humans—are the ones who embody that classic ideal. They are the ones who can think, fight, analyze, feel, and cooperate. They are the competent ones in a universe run by decadent, overgrown children.

AIt’s a humanist-capability vision. It’s Clarke’s awe and Heinlein’s grit fused together into a single, magnificent argument that the future belongs not to the narrow specialist or the powerful fool, but to the complete human being—the one who can both quote Shakespeare and calculate a orbital trajectory. Simmons built a cathedral to that idea. And he built it out of every damn thing he knew.

Leave a Reply