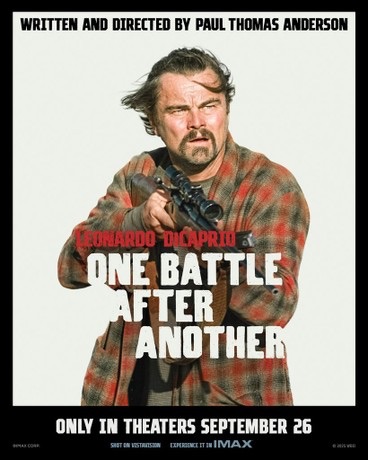

I went to see One Battle After Another, and it hit that this was a collision of auctorish chaos, authorish genius, and auteurial precision—a live-fire test of what happens when a literary virus meets a human operating system. The film is based on Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland—one of his most authorish works, a sprawling, jittery tangle of counterculture ghosts, FBI paranoia, and psychedelic detritus. Pynchon is an Auctor, pure and untranslatable: his novels aren’t just read, they execute in the reader’s nervous system, leaving code running in the background that reshapes how you parse reality.

Watching the film I could feel Pynchon’s Auctor’s virus being reshuffled, passed through a Paul Thomas Anderson auteurish rendering engine. The sprawling chaos of Vineland—its half-remembered plots, its anarchic pulse—gets compressed, disciplined, and refracted through PTA’s cinematic grammar: the camera becomes a tactile sensor, the characters act as bio-feedback loops, the narrative itself tracked and stitched like a neural net.

And it made me think about the difference between an Auctor, an Author, and an Auteur. This isn’t just academic taxonomy—it’s the root-level code of culture, the way creative energy moves through the system, how it gets digested or rejected, how it mutates over time. Understanding that difference explains everything from why Kafka died in obscurity to why a singular filmmaker can reshape the signals of a sprawling novel into something both recognizable and utterly new.

1. THE AUCTORS: ONTOLOGICAL HACKERS

Think of an Auctor not as a writer or painter, but as a coder who writes a new operating system for reality. The Latin auctor means “originator,” “promoter,” “one who causes increase.” But that’s too gentle. An Auctor is an ontological saboteur. They don’t play the game better; they change the rules of the game itself. They hack the grammar of perception.

Forget the romanticized “tortured genius.” That’s a sentimental fairy tale for mass consumption. The Auctor is a more terrifying and precise entity: a zero-day exploit in the human sensorium. They don’t have ideas; they have discoveries. They stumble upon a flaw, a backdoor in the shared hallucination we call reality, and they weaponize it.

Their work is not stylistically different; it is categorically different. It introduces a bug in the consensus reality that, once encountered, cannot be patched. The system must either crash or reconfigure itself around the new code.

This isn’t innovation. Innovation is Apple putting a better camera in a phone. This is revelation of a kind that breaks the phone entirely and suggests we communicate through synaptic pulsations instead.

Their signal is catastrophically mis-timed, so alien it either triggers immediate rejection—as with the boos at the premiere of The Rite of Spring—or lies dormant as a sleeper agent in the cultural mainframe, only activating posthumously. Contemporaries simply lack the firmware to run the software.

The failure is temporal. The host system—contemporary culture—doesn’t yet have the necessary definitions in its library. It’s like trying to run a quantum algorithm on an abacus: the system throws a fatal exception, a bluescreen. The outrage at The Rite of Spring wasn’t mere dislike; it was the sound of a thousand psychic immune systems detecting a pathogen and screaming in unison. The music wasn’t “bad”—it felt like rhythmic and harmonic violence, an assault on the order of things itself.

The Target is Not the Medium, But the Mind: The painter’s target isn’t canvas; it’s the optical nerve and the visual cortex. The writer’s target isn’t paper; it’s the language centers and the model of the world they sustain. The Auctor writes a virus in the native language of perception itself.

Kafka didn’t just write about anxiety; he compiled a new executable for narrative. In his universe, the logic of bureaucracy and guilt becomes the fundamental law of reality itself—a bug report from a future that hadn’t yet arrived. Before him, narrative grammar obeyed rules of cause and effect, character motivation, and a world that, however strange, remained potentially knowable. Kafka injected a new syntax where the rules are opaque, punishment is preordained, and central command—The Castle, The Law—is omnipresent yet inaccessible. You don’t simply read Kafka; you are infected by him. A latent Kafka-process begins running in the background of your mind, reinterpreting every encounter with bureaucracy and authority through his corrupted framework.

Kafka was not a prophet of bureaucracy but its anatomist. He revealed its cosmic scale: the modern world governed not by kings or gods but by an infinite, indifferent, nonsensical Administration. His work is the holy text of an age where God has been replaced by a Help Desk that is permanently closed. His final hack was the instruction to burn his manuscripts—a command to delete the virus. Fortunately, that line of code was never executed.

Van Gogh was not simply a painter of sunflowers; he was a programmer brute-forcing a new graphics driver for the human eye. His brushstrokes weren’t a matter of style but a protocol for transmitting raw electromagnetic emotion onto a flat surface. Where the prevailing driver of his time was calibrated for photographic realism—for stable, representational worlds—Van Gogh bypassed representation entirely and streamed sensation directly to the display. Each stroke is not a depiction of a cypress but a packet of data carrying “cypress-ness”: the swirling, burning, vital energy of the thing itself.

The market’s firewall—the gallery system, the critics—detected this as a denial-of-service attack on good taste and blocked it. He wasn’t selling a product; he was deploying a protocol. A protocol so alien that it would only boot properly decades later, once the cultural operating system had finally caught up.

Lovecraft was an Auctor. Not a conventional writer, but a compiler of forbidden routines, a virus seeded into the cultural kernel before any firewall existed. His sentences didn’t merely describe dread—they executed it. Every archaic clause, every suffocatingly precise adjective, installed subroutines in the reader’s mind, initializing terror functions their neural architecture was never designed to run. Those who read him became hosts for a daemon silently observing, calculating, and reshaping their perception of reality.

His worlds were operating environments, not fiction. Arkham, Innsmouth, the Plateau of Leng—they acted as nodes in a network of cosmic authority. Each entity, from Nyarlathotep to the sluggish, cyclopean Shoggoths, was a protocol violation, a strain of code the human OS could not parse. Minds attempted to allocate memory to them and failed. Stack overflows of awe and nausea occurred. That creeping, existential panic was no decoration—it was the result of a program running correctly, a glitch intentionally left unpatched.

The hallmark of Lovecraft as Auctor was that he never courted digestion by the host system. Unlike Authors, whose work the culture could metabolize, or Auteurs, whose vision could be repackaged for consumption, Lovecraft’s writing remained fundamentally alien. Each story completed its execution and left the host infected, with recursive loops of fear nested in the cortical architecture. He functioned as a kernel-level threat: invisible, unstoppable, a literary rootkit that persisted through generations, mirrored in the subconscious of every reader who booted the system and left it running.

Picasso and Stravinsky were rare cases of forced updates—hacks so powerful they executed in real time, bricking the old systems of perspective and harmony as the audience watched. These were rare, high-intensity events. They didn’t just introduce a bug; they forked the entire cultural reality. The riot wasn’t mere scandal; it was the sound of reality itself being overwritten.

Picasso recognized that the camera had made representational painting obsolete as documentation. His hack was to rewrite perspective itself, forcing the eye to process multiple dimensions at once—closer to how objects exist in the mind. Stravinsky did the same with time, replacing predictable meter with rhythmic primes and dissonances that felt ancient, even savage. These weren’t gradual shifts absorbed by history; they were fork bombs, multiplying processes until the cultural operating system crashed. Their work didn’t wait for posthumous recognition because their exploits triggered an immediate, traumatic system update.

<>

The Implication: The Auctor is the true source of cultural singularity. The middle-class mindset—obsessed with comfort, recognition, and “good taste”—is biologically incapable of processing their work. Taste is a backward-compatibility feature. Auctores are incompatible with everything. This is not a glamorous life. It is a pathological condition.

The Auctor is a canary in the coal seam of the future, suffocating on a gas the rest of us can’t yet smell. They are not “ahead of their time”; they are from a different time, one that hasn’t happened yet. They are exiles living in the present. The middle class, the great engine of cultural stability, is their natural predator. The middle class thrives on predictability, legibility, and shared signs of status (“taste”). The Auctor makes everything illegible. They are the ultimate party-crasher, pointing out that the walls of the mansion are made of cardboard and the host is a hallucination.

The “cultural singularity” is not a future event. It’s a recurring, localized phenomenon that happens every time an Auctor’s hack achieves critical mass. It’s the moment when the collective consciousness is forcibly rewired, and there is no going back. There is pre-Kafka and post-Kafka. Pre-Einstein and post-Einstein. Pre-World Wide Web and post-World Wide Web.

They are the true source of all genuine change. Everyone else—the Authors, the Auteurs, the curators—are merely building beautifully in the new worlds that the Auctores, at great personal cost, first dared to imagine. They are the gods of the cultural stack, and we are all just running their legacy code.

2. THE AUTHORS: ELEGANT CODERS

The “Author” is where the myth of manageable genius lives. It’s the space where culture does its quality control, where it takes the raw, terrifying singularity of the Auctor and turns it into a sustainable product.

The Author is a master developer working within a stable, established operating system. They did not write the OS; they write breathtakingly elegant, complex, and profound applications for it. Their innovation is in style, narrative architecture, and thematic depth, not in fundamental ontology.

Forget the revolutionary. The Author is the brilliant systems architect brought in after the revolution to make the new operating system actually livable. The Auctor gives you Unix—a powerful, cryptic, foundational grammar. The Author gives you the Apple Macintosh: a beautiful, intuitive, and deeply humane interface built on top of that terrifying power.

They are the gold standard of literary and artistic achievement within a paradigm. Their work is legible, appreciable, and can be canonized by the taste-making classes because it represents the pinnacle of what is already understood to be possible.

They are masters of constraint. Their genius is not in burning down the library, but in writing the most breathtaking books that can possibly fit on its existing shelves. High probability of contemporary success and acclaim. Their work is a feature, not a bug. It enhances the system without threatening a total system wipe.

The Mechanics of Elegance:

1. Exploiting the Platform’s Full Potential: The Auctor builds the processor. The Author writes the software that makes you gasp at what the processor can actually do. They work within the established syntax—the three-act structure, the sonnet form, the harmonic rules of tonality—but they find hidden op-codes, they overclock the narrative, they push the defined parameters to their absolute limit without causing a kernel panic.

2. The Art of the Patch, Not the Fork: An Author’s innovation is often a brilliant patch to a known bug in the human condition. The bug might be “how do we represent consciousness?” Proust patches it with involuntary memory. The bug might be “what is the texture of post-war alienation?” Fitzgerald patches it with the green light and the valley of ashes. They don’t solve the problem; they provide an elegant, temporary fix that becomes the new standard.

3. Legibility as a Feature, Not a Bug: This is crucial. The Author’s work is meant to be understood, appreciated, and canonized. Its complexity is a surface complexity, like the intricate circuitry of a masterfully designed amplifier—it’s there to produce a clear, powerful signal, not to be mysterious for its own sake. This legibility is what makes them the darlings of the academic-culture complex. You can build a syllabus around an Author. You can’t build a syllabus around an Auctor; you can only be ambushed by one.

Jane Austen was a master of the social simulation game. She did not invent the novel of manners; she perfected its code, finding exploits and depths previous developers never imagined. Think of her not as a novelist, but as a developer for the “Early 19th Century British Gentility” simulation game. Her characters are AI agents with defined parameters: wealth, lineage, wit, vulnerability. The plot is the engine running these agents against each other, testing their compatibility, exposing their flawed logic. She didn’t invent the rules of this society; she revealed its underlying physics with the precision of a mathematician. She found the exploits—the strategic marriage, the power of a well-timed letter—and wrote the definitive strategy guide. Her work is the ultimate in-system achievement.

Nabokov was a programmer’s programmer. Wrote meta-applications that commented on their own code, dazzling in their complexity and beauty, all while running on the recognizable hardware of the novel form. Nabokov is the coder who writes a stunningly beautiful video game, but then also publishes the source code with witty, devastating annotations. He is constantly reminding you that you are holding a book, that he is pulling the strings, that language is a game. But the game is so sublime, the prose so electrically alive, that the meta-commentary doesn’t break the immersion; it becomes a higher form of immersion. He is playing with the novel’s OS, not trying to replace it. He is the ultimate power-user.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote the most poignant and tragic plugin for the “American Dream” OS. He was the poet of the API glitch. His great subject was the catastrophic failure of a single cultural function: acquireWealth()—which should have returned happiness, but instead produced NULL or, worse, corrosive despair. His novels are elegant error logs, documenting the buffer overflow between aspiration and reality. Fitzgerald never questioned the existence of the American Dream OS; he simply revealed, with heartbreaking precision, what happens when its core promise fails to execute.

The Implication is authors are what the culture thinks it means by “genius.” They are safe geniuses. Their work becomes the curriculum. It is the basis for what we call “taste”—the ability to recognize and appreciate a masterful execution within a known framework. This is not a minor thing. It is just not an ontological thing. The Author is the figure that allows culture to safely metabolize brilliance. They are the “genius” that can be taught in an MFA program, awarded a prize, and discussed on a panel. They prove that excellence is possible within the system. This is a profoundly comforting idea.

This is why they are the cornerstone of Taste. Taste is not about recognizing the new; it’s about recognizing the best of the known. It’s a system of validation. To appreciate Jane Austen is to signal that you understand the nuances of a shared cultural language. To appreciate Kafka is to admit that the language itself might be nonsensical—a far more threatening proposition.

The Author is the hero of the stable state. They are the proof that a civilization has reached a point of maturity where it can refine its own artifacts to a high gloss. But they are also a sign that the revolutionary energy of the Auctor has been successfully contained, packaged, and put to work decorating the walls of the empire. They are necessary, magnificent, and ultimately, a symptom of a culture that is managing its assets, not forging new ones.

3. THE AUTEURS: VISIONARY SYSTEMS ARCHITECTS

The Auteur is the most precarious, and therefore most telling, figure in our entire taxonomy. They are not the mad scientist in the garage; they are the rogue engineer inside the megacorp, subverting the corporate toolkit to build something that smells like a soul.

The Auteur is a hybrid entity, a phenomenon of the age of mechanical—and digital—reproduction. They are often not writing original code from scratch. They are curators, assemblers, directors. But to call them mere curators is to miss the point entirely.

Forget the romantic artist in a garret. The Auteur is a guerrilla warrior operating deep within enemy territory: the Culture Industry. Their primary skill is not invention, but appropriation and reassembly. They are master salvagers, taking the prefabricated components of mass culture—the genre tropes, the familiar scripts, the historical bric-a-brac—and welding them into a structure that bears their unique, unmistakable signature.

An Auteur takes existing code—a novel, a script, a genre trope—and recompiles it through the sheer force of a coherent, uncompromising vision. They impose their own signature grammar onto the material. The source is subsumed into their system. The result is not a faithful translation; it is a manifestly branded product.

This isn’t mere curation. Curation is for librarians and playlist algorithms. The Auteur performs a kind of alchemical possession. They don’t just select the source material; they ingest it, and what they excrete is something new, something that could only have come from their own digestive system. Institutional, contemporary, and highly visible. The Auteur’s power is their ability to operate within the machinery of production (studios, galleries, publishers) while stamping the output with a personal cryptograph. They are brands themselves.

1. The Signature Grammar: Every true Auteur develops a personal syntax—a set of formal tics and obsessions so consistent it becomes a dialect. Kubrick’s grammar was the glacial tracking shot, the symmetrical composition, the use of existing classical music as ironic or monumental counterpoint. PTA’s grammar is the restless, probing camera, the dense soundscapes of overlapping dialogue and curated pop songs, the fascination with desperate, charismatic men building pathetic empires. This grammar is their brand, their cryptographic signature. It’s how you know who’s talking, even when the words are someone else’s.

2. Operating Within the Machine: This is the key differentiator. The Auctor is off-grid. The Author works in a sanctioned studio. The Auteur infiltrates the factory. They secure funding from studios, use union crews, and deliver a product that, on paper, fits a market category—a horror film, a period drama, a sci-fi epic. But the product they deliver is a Trojan Horse. It looks like a conventional offering, but it’s packed with their own ideological and aesthetic army. They are institutional saboteurs.

3. The Raw Material of Taste: The Auteur is a connoisseur. They have impeccable taste in source material. Kubrick didn’t pick random novels; he picked ones with a potent central metaphor he could exploit. PTA mines specific, gritty veins of American history and literature. But for them, taste is the starting block, not the finish line. It’s the ore they smelt into steel. The cultural tastemaker stops at acquiring and displaying the rare ore. The Auteur forges it into a weapon.

Stanley Kubrick is the archetype—the master renderer. Give him a sprawling metaphysical short story (The Sentimel), a horror potboiler (The Shining), or a dystopian shock-text (A Clockwork Orange), and he feeds it through the Kubrick engine. The output is unmistakable: cold, monumental, precise. Kubrick was less an adapter than a clinical possessor, the ultimate system architect. He would take a pulpy, visceral source and subject it to a process of radical sterilization and architectural reinforcement. King’s Shining is hot, emotional, haunted; Kubrick’s is cold, psychological, engineered. The Overlook Hotel isn’t just a haunted house but a geometric paradox, a meticulously designed psychic trap. He didn’t “adapt” the book—he performed an autopsy on it. He excised the flesh of character and melodrama, extracted the kernel of cyclical madness, and rebuilt it as a new engine, humming with inhuman clarity.

Kubrick’s genius was parasitic and generative at once. The source material lies as a corpse on the slab, but the film he constructs is a perfect android assembled from its parts: uncanny, unyielding, alive in a way the original never was. His films don’t just tell stories—they recompile them, rewriting the code until they become self-contained operating systems, environments where human beings wander like test subjects inside the vast machine of his vision.

Paul Thomas Anderson is the perfect contemporary exemplar. He takes historical episodes (There Will Be Blood), postmodern novels (Inherent Vice), or loose cultural anxieties (Licorice Pizza) and forges them in the furnace of his cinematic grammar—sinuous tracking shots, immersive soundscapes, actorly possessions. He is not an inventor of the cinematic language, but he speaks it with an accent so thick, with a rhythm so unmistakably his own, that the material becomes inseparable from his voice. For PTA, taste is not the product but the raw material.

He is less an auteur than an anthropologist of Weird America, a collector of spiritual decay and cultural detritus. He doesn’t create myths so much as exhume and reassemble the fractured ones already embedded in the national psyche. There Will Be Blood reframes the capitalist oilman as a biblical patriarch devoured by hatred. The Master anatomizes the desperate hunger for belief systems in the postwar void. Boogie Nights maps the contours of desire, shame, and reinvention in the underworld of pornography. In every case, the story is less “told” than lived through a process of cinematic possession: the camera roves like a divining rod, the performances swell and rupture as if channeled from elsewhere.

His films are residues of immersion. They feel less authored than inhabited, as if he allowed himself and his collaborators to be overtaken by the milieu until the work emerges like a found artifact. If Kubrick was the cold system architect dissecting his sources, PTA is the field anthropologist, half-scholar, half-shaman, returning with cinematic fossils that seem both excavated and newly forged.

The Implication is the Auteur is the last bastion of visionary authority in a culture drowning in curation. They prove that agency is not about originality of parts, but about the ferocity of the integrating vision.

<>

The middle class, once the traditional audience for art and literature, is disappearing. They abandoned the Auctores long ago, unable to stomach the raw, alien shock of true originality. Now they are abandoning Authors, too—the ones who translated vision into accessible form. Even the Auteurs, who once slipped visionary toxins into digestible packages, are being discarded.

What remains is a fixation on “taste” as a substitute for soul. But this is not cultivated discernment; it is simulated taste, generated by algorithms, amplified by influencers, and consumed as a desperate signal of belonging.

Culture no longer celebrates architects—the builders of new forms—but concierges: those who know the best restaurant, the hottest DJ, the most obscure band. Consumption has replaced creation as the marker of identity. We have become a society that prefers being served to building for ourselves.

This abandonment plays out in the body of culture like a failed immune system. The Auctores were rejected outright—too alien, too indigestible. The Authors were once welcomed, absorbed, and metabolized into the body of the culture. The Auteurs tricked the system: they packaged experimental vision inside familiar forms. But even they are being filtered out now, reduced to surface style, stripped of their visionary core.

In place of creation, we get recursion—a pyramid scheme of cultural capital. The algorithm recommends the curator. The curator celebrates the DJ. The DJ plays the songwriter’s track. The songwriter cites a half-forgotten Auctor.

At every step, the meaning thins, the signal dilutes. The ontological shock of the Auctor becomes, at best, a retro aesthetic, a mood board, a filter. The signifier floats free of the signified. The surface gleams; the engine rusts to dust.

Paul Thomas Anderson is not a cure but a lone holdout. He shows that a singular human vision can still imprint itself on the industrial product. But he is an exception that proves the rule: the middle class has no patience even for him.

The true Auctores survive in the margins—through AI promptcraft, viral ARGs, bio-hacked performances. They operate in mediums not yet recognized as art, ignored as noise by the system.

The cultural body now suffers from an autoimmune disorder. It attacks its own future while mistaking its decay for vitality. The middle class, once a carrier for art, has turned into its undertaker.

The question remains: what will you do with this knowledge before the system collapses completely? Build a bunker? Or attempt a new patch?

The clock is ticking.

Leave a Reply