I’ve been living in California since 2007. I used to come here before, and I always had this feeling that it’s like people come here because of an album. Some people came for Crosby, Stills & Nash. Some people came for Hotel California. Some people came for Linda Ronstadt, some for The Grateful Dead. I’m assuming at the time there were some who came for The Mamas and the Papas. It’s like you arrive, and that becomes your imprint, like a duckling. Then you’re condemned to circle around the contours of that album and that style. If it was The Grateful Dead, maybe you’d branch into the jam band thing, but mostly you’d just keep orbiting the Dead. If you were into The Eagles, maybe you’d drift toward Buffalo Springfield and Poco. If it was Crosby, Stills & Nash, maybe Neil Young. But you still carry that first imprint. I’m sure some people came for Tom Petty, or even The Cars. But whatever it was, that imprint becomes the precondition for this whole retro era we’re in now.

That’s the paradox of California: it’s both a place and a projection screen. Unlike New York or Chicago, which forged scenes out of density and friction, California absorbed people who came west already carrying an album like a talisman. A Hotel California person builds their California experience around sun-baked, decadent dreams of the coast. A Deadhead centers theirs on community, travel, and transcendence (with or without the drugs). A Laurel Canyon acolyte sees everything through the lens of harmony, introspection, and acoustic guitars.

This act of cultural imprinting works like a genetic bottleneck. Instead of inventing something entirely new, people repeat and refine the album that brought them here. Whole ecosystems form around those blueprints: canyon folk scenes, jam-band circuits, desert rock revivals, retro-pop enclaves. Retro culture isn’t just nostalgia — it’s the endless re-enactment of that first imprint. And California, with its sunshine, its openness, and its mythic promise, is where those imprints took root and hardened into style.

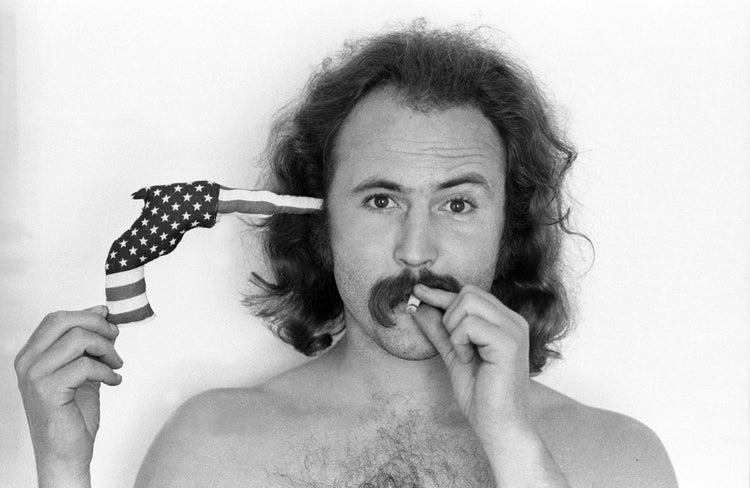

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Laurel Canyon was ground zero for imprint culture. The Mamas and the Papas sang the invitation, Crosby, Stills & Nash embodied the harmonies, Joni Mitchell wrote the private diary, and the Eagles polished the sound into a radio-ready empire. People who imprinted on this wave never really left it. They could dabble in adjacent sounds — Neil Young’s rustic melancholy, Poco’s country rock — but they were bound to that acoustic, harmony-laden ideal of California.

For others, San Francisco was the imprint. The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Santana: this was California as transcendence, improvisation, and endless motion. A Deadhead who imprinted on American Beauty or Europe ’72 could spend decades chasing the sound, drifting into jam-band culture, but never breaking orbit. This imprint was less about polish, more about community and cosmic wandering — and it still sustains festivals and subcultures to this day.

Then something different happened. By the late 70s, a new kind of California imprint arrived: Devo. They weren’t Laurel Canyon or Haight-Ashbury — they were industrial sarcasm, a soundtrack for de-evolution. Devo’s California wasn’t sunshine and harmony; it was paranoia, plastic, and absurdity. For those who imprinted on Devo, the blueprint wasn’t community or canyon dreams but irony, alienation, and technological anxiety. That imprint still survives in synth-pop revivals, ironic art-rock, and the whole indie-pop posture of detachment.

By the late 80s, Los Angeles supplied its own mutations of imprint culture. Jane’s Addiction imprinted people with a hybrid of art rock, funk, and seedy Hollywood decadence — a West Coast counterpoint to New York’s Sonic Youth or CBGB lineage. They gave California an imprint of urban chaos, tattoos, and postmodern ritual, all with the smog and freeways in the background.

Guns N’ Roses offered another, equally sticky imprint: the nihilist glamour of Sunset Strip hard rock. For those who imprinted on Appetite for Destruction, California wasn’t the canyon or the jam circuit — it was leather, sleaze, violence, and spectacle. And just like with earlier waves, their followers still circle that sound today, unable to escape the orbit of Slash’s top hat and Axl’s shriek.

Taken together, these waves reveal the same pattern: people come to California, imprint on an album, and then re-enact it. Each generation thinks they’re discovering the state anew, but in practice, they’re repeating the ritual of their predecessors — replaying their chosen mother-album over and over in slightly new arrangements.

That’s why California culture always feels retro. It’s not just nostalgia — it’s an ecological fact of imprinting. The canyon harmonies, the Dead’s improvisation, Devo’s absurdity, Jane’s Addiction’s chaos, Guns N’ Roses’ sleaze: these are fixed genetic codes. Newcomers arrive and pick their imprint. And from then on, they’re condemned to orbit it — ducks circling the shadow of their mother goose.

The Tech Imprint

California isn’t just an album-imprint machine; it’s a tech-imprint machine too. Just as people once arrived chasing their Hotel California or their American Beauty, people now arrive chasing their idea of Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, or Mark Zuckerberg.

earnestly quoting Thiel, Andreessen — reciting these names as if they were incantations, as if the Valley still offered the conditions that made them possible. But the situation that produced those figures doesn’t exist anymore. Cheap garages are gone, overheads are crushing, failure is fatal. What remains is the ritual of imitation: newcomers quoting the archetypes of an older age, chasing ghosts in a landscape that no longer has the room — or the rent — for something truly new.

The problem is, the conditions that once made these imprints generative are gone. In the 1960s and 70s, both in music and in technology, California offered cheap rents, open space, and a margin for error. Experimentation was possible because failure wasn’t fatal. A band could live on beans in Laurel Canyon while working out a new sound; a couple of engineers in a garage could build a circuit board that changed the world.

Now the rent is too damn high. The overheads kill experimentation before it starts. You can’t afford to fail, and without failure, you don’t get invention — only iteration. Tech, like music, has entered its retro phase: startups re-enacting Jobs’ garage myth, VCs replaying the same funding theater, founders chasing the same archetypes.

Just as the canyon kids are condemned to keep strumming their first imprinted chords, the Valley kids are condemned to re-enact their origin myths. California still produces, but not spectacularly new things — only variations on old templates. The golden age of experiment has been priced out.

Taken together, music and tech reveal the same pattern: California no longer invents from scratch. It recycles its own myths. The canyon folkies, the Deadheads, the Devo kids, the Guns N’ Roses acolytes — all circling their first imprints. The Jobs disciples, the Musk imitators, the startup founders re-enacting the garage myth — all circling theirs.

California has become a retro state, not because it lacks talent or imagination, but because the conditions that allowed newness have been erased. The rents are too high, the overheads too crushing, the stakes too large to allow real risk. In the 60s and 70s, you could live cheaply, fail often, and stumble into something spectacularly new. Today, the economics force conformity and replication.

So California keeps producing echoes — echoes of albums, echoes of startups, echoes of golden ages. It’s still glamorous, still magnetic, but the shine is archival. People still come west chasing a dream, but what they find is a museum of their own imprints, carefully preserved and endlessly replayed.

The Curator’s Trap: Performance as Diminishing Returns

This cycle of imprint and re-enactment has logically birthed California’s dominant modern archetype: the Curator. When the economic runway for true experimentation vanishes, the most viable path is not to invent a new sound but to perfect the performance of an existing one. The state’s cultural energy has shifted from raw creation to sophisticated curation.

We see it everywhere: the modern Laurel Canyon resident who may not write a new “California Dreamin’” but expertly crafts the perfect playlist, the artisanal aesthetic, and the vintage wardrobe, performing the idea of the canyon for a digital audience. The tech founder, unable to replicate the conditions of the garage, instead meticulously curates the signifiers of innovation—the minimalist office, the disruptive rhetoric—re-enacting the Jobs imprint for investors.

But this is not a neutral act of preservation. It is a sleight of hand that turns people into infrastructure. Each new generation, moored to the hyperreality of a chosen past, becomes the maintenance crew for a fading dream. Their lives, tastes, and creative energies are no longer directed toward invention but toward upkeep—sustaining the aesthetic and economic structures of the very imprint that trapped them.

The acolyte isn’t just strumming an inherited chord progression; they are generating content for the tourism board, justifying the value of a multi-million dollar canyon home, becoming brand ambassadors for a lifestyle they can scarcely afford. They are the gears in California’s retro machine, their personal identities commodified into the steady, predictable output of nostalgia. This is the paradox of diminishing returns: the more fervently the imprinted re-enact their blueprint, the more they solidify the conditions that make original creation impossible.

The state no longer inspires artists and inventors; it produces high-end curators and maintenance engineers for its own mythology. People arrive seeking freedom and instead find a pre-written script, their individuality reduced to a choice of which vintage imprint to perform. The sunshine is real, the ocean is real, but the culture is a beautiful, self-replicating ghost, sustained by the very souls who came west to find something alive.

Leave a Reply